The word mosaic comes from the Greek mousa (muse). The Romans believed that mosaic was such an exquisite art that could only be the muses that inspired the artists who created them. Following Hebrew etymology, artist Daniel Yacubovich reports me that it could derive from Moses because of the similarity with the name and in Arabic language it is Musa; he remarks that the Tablets of the Law, made of stone, when the prophet came down from the mountain and broke them, were shattered on the ground, at a symbolic level, maybe it was one of the first “myths in deconstruction” in a se non è vero, è ben trovato. In fact, to make a mosaic, first, you have to break much larger stones into tiny pieces. Mosaics were made with cubes of naturally colored stone (marble or limestone), terracotta or glass called tesserae, which were laid side by side in a bed of cement or plaster and with them all kind of figures can be formed. Roman and Byzantine culture have provided the most prominent mosaics in Art History. There are many techniques for cutting, combining, and placing tesserae on floors, walls, vaults, and domes. The most common are: opus tessellatum, opus regulatum, opus vermiculatum, opus musivum, opus palladianum, opus sectile, opus classicum and opus circumactum. (Picture above: Roman mosaic (4th century). Akaki, Cyprus. Photo: Cyprus Department of Antiquities).

Antioch and Daphne (1st and 2nd centuries). Baltimore Museum of Art, Maryland. Foto: TripAdvisor

Fourteen hundred years ago, the mosaics on display that hang on the walls of the Schaefer Court at the Baltimore Museum of Art, were floor pavement in fine villas in the city of Antioch and its garden suburb, Daphne. The affluent citizens of Antioch spent their summer months in this village, were natural springs filled the ponds and fountains of their fine country houses. These ancient Roman cities were located near the present-day border between Turkey and Syria and these mosaics were produced between the 1st and 6th centuries. Today, Antioch (modern Antakya) is part of the province of Hatay, in Southern Turkey. Antioch was a splendid city well-known in ancient times as “the fair crown of the Orient”. Situated on the Orontes River, just inside the eastern edge of the Roman Empire, Antioch was an important stop along the major trade route linking the East and West: the silk road. Camel caravans carrying goods from the East stopped at Antioch to exchange wares with sea traders from the Mediterranean. A cosmopolitan city where Asians traded with European, a crossroads of cultures where traditions and religions pagan, Jewish and Christian coexisted.

Birds in rinceau (526–540). Antioch. Princeton University Art Museum, New Jersey. Foto: PUAM

The tesserae used in the Antioch mosaics are made of marble of various colors. Workman sawed sticks of marble off the large blocks, then used hammer and chisel to chip away irregularly-shaped squares or rectangles with different sizes depending on the design to be made. Because of the marble, the mosaics floors were durable, easy to wash and cool on the heat of summer. In addition, they provided large surfaces which could be decorated with images of mythological heroes, allegorical figures, flowers, birds and beasts or geometric patterns. The figural images were created by masters craftsmen skilled in adapting popular Roman wall paintings to the mosaic medium.

Being a “mosaic” of cultures, the mosaics of Antioch and Daphne depict their different mythological traditions throughout the centuries, we can see sea nymphs, tritons, satyrs, gods and goddesses of the Greco-Roman tradition and the rams and royal lions of Persia. For example, the lion was a symbol for strength in ancient Persia, so the presence of the lion in this mosaic implies that the Persian culture was influencing a society that had always considered itself part of the Roman Empire. The large mosaic where the lion comes from in the picture above was divided into 86 parts and contained images of fruits and flowers, birds, fish, antelopes and even pumpkins to suggest the great abundance of flora and fauna in the area.

In another large mosaic,The Beribboned Parrots, thirty parrots sporting ribbons may appear festive to the modern eye, but in the 5th and 6th centuries they were a symbol of the royal Sasanian Dynasty of Persia, Antioch’s neighbor to the east. Parrots wearing the pativ (Persian ribbon) were associated with the Zoroastrian religion and were thought to avert “the evil eye”. Persian motifs, such as the beribbonned parrot were fashioned into jewelry and woven on rugs throughout the Roman world. Mosaicists in Antioch took notice and included the motif in their own repertoire of designs.

The mosaic above is one of six extant fragments that formed part of the border of a large floor mosaic, nearly 700 square feet in size. The fragments were dispersed to several museums and this one, at the Worcester Art Museum, depicts two brilliantly colored peacocks face a basket laden with grapes. In the Roman world peacocks were linked with immortality and eternal life, probably because they shed their tail feathers in winter and renew them each spring, but also they were very popular in the early Christian mosaics, a symbol of resurrection, which may refer to the growing strength and power of the Christian church in the area, dating from the 6th century, already in the Christian era. The great skill of the mosaicists is appreciated in the waves and especially the ribbons that frame the figures, the graded treatment of the colors and the dark background produces a three-dimensional illusion of a long fluttering ribbon.

The Spring (2nd century). Daphne. Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York. Photo: MET

The figures are usually framed by exquisite and intricate geometric designs: meanders, waves, striped triangles, rhombuses, dots, ribbons, circles, stars, the rinceau (a continuous roll of foliage) … made by the apprentices. Some are of the so-called mosaic-carpet type because their grid-like lattice patterns resemble Persian rugs.These mosaics are exceptional because they show an iconographic journey of five centuries, with a pagan repertory but in some scenes the style is already to some extent Byzantine, and it is possible that the animals and hunting scenes depicted on many of them may even have had an esoteric Christian significance, in that they were designed to depict the Christian paradise, according to the Baltimore Museum of Art explanation.

Bust of Tethys (3rd century). Daphne. Baltimore Museum of Art, Maryland. Photo: Wiki

Unfortunately Antioch did not survive. In 526 a severe earthquake destroyed many of its buildings and subsequent invasions by Persian armies reduced the city to rubble. Its fine mosaics pavements lay buried and forgotten. In 1932 archeologists began an excavation of the site, not knowing what they would find. The project was sponsored jointly by Princeton University, the Worcester Art Museum, Dumbarton Oaks in Washington DC, the Musées Nationaux de France and the Baltimore Museum of Art. So, between 1932 and 1939, laborers unearthed more than 300 mosaic pavements, breaking up the larger panels and lifting them in peaces. But the mosaics were not put together again. So, this practice, now unthinkable, led to large mosaics fragmenting and dispersing. Therefore, now we can see loose panels in the aforementioned museums. The Syrian government generously donated many of the mosaics and other excavated objects to these museums where they are now on display. What they left is exhibited at the Hatay Museum, in Antakya.

Sea Nereid (2nd century). Daphne. Baltimore Museum of Art. Photo Mike Fitzpatrick

Some of the pavements were badly damaged after fourteen centuries underground, between groundwater and shovels and plowshares that farmers had unknowingly inflicted on them, causing additional damage. They were restored, and specifically on the mosaics that are exhibited in the Baltimore Museum of Art, rather than introducing tesserae in the areas that they had disappeared, it were restored by inpainting over a fine plaster wash suggesting the original design. The problem is the brushstrokes, which are black, can be seen at first sight, so the result is not good, I don’t think today restorers would proceed in that way, restorations are not invasive and the space would have been left empty. The Antioch excavations were of a great magnitude, involving Western museums and taking away much of the material. An archaeological operation of this kind would not be possible today. Present-day Turkey would not donate the mosaics found as Syria did. Although it can be said, on this delicate and controversial subject, that the mosaics have been preserved.

More Roman mosaics

It seems that mosaics had been used by the Sumerians as early as the third millennium B.C. to embellish architectural surfaces but they are unknown as well as pebble mosaics were made in Tyrins, in Mycenean. The professor of the University of Cambridge, John Gage, in his book Color and Culture, wrote that “the pebbles of the Early Greek mosaics gave way to regularly cut tesserae (cubs) about the third century BC, and soon the naturally colored stone tesserae were supplemented by a sprinkling of artificially colored terracotta or glass which brought a vast increase in chromatic range.” Thus, over the centuries, the Hellenistic Greeks and Romans perfected the technique to the point of being able to reproduce paintings.

Academy of Plato/Seven Philosophers (100-79 a.C). Pompeii. Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples. Photo: Wiki

In the Roman world most mosaics were laid on the floor. They form one of the most well-preserved and widespread types of Roman art, found throughout the Roman Empire from Britain and Spain in the west to Jordan and northern Mesopotamia in the east. They were used in public buildings such as Roman baths and marketplaces, the majority of mosaics, however, decorated private buildings, both large city houses and villas in the countryside or by the sea. Mosaics were expensive and slow to make, although they would thereafter require little maintenance and could be expected to last a lifetime. They were made of marble tesserae although rich in gradations, lacked brilliance as it was limited to the various types of colored marble found in nature. The Romans knew about glass, but they did not exploit it for their pavements. The floor mosaics a provide valuable information about the tastes, traditions and common objects of the wealthy houses that commissioned their production, as we have seen in Antioch and Daphne. The subjects were diverse. On one hand, were pagan in character: gods and episodes of mythology accompanied by motifs of flora and fauna and geometric designs, as well as war episodes or historical and cultural events. Mythological scenes were popular, presumably because they were timeless and familiar classics, though they may also have been deliberately chosen to signify the owner’s cultural level and taste. Scenes of what may be called daily life—activities such as hunting, fishing, and circus races and games involving gladiators, other fighters, or animals—also had great appeal.

Segnior Julius (5th century). Cartago. Bardo National Museum, Tunis. Photo Boyd Dwayer

Archaeologists have unearthed a multitude of mosaics throughout the territories that made up the Roman Empire. Many of the mosaics were removed and set up in museums around the world. Here’s a tour to the major museums that preserve magnificent mosaics that I have had the opportunity to visit over the years and I remember well. The Bardo Museum, in Tunis, houses the largest collections of Roman mosaics in the world, thanks to excavations at the beginning of 20th century in various archaeological sites in the country including Carthage, Hadrumetum, Dougga and Utica. They represent a unique source for research on everyday life in Roman Africa. They are exceptionally well preserved mosaics that occupy more than half of the museum’s display space. After a century of Punic Wars, with the Carthage city destroyed in the 2nd century B.C even destroying its fields sowing them with salt, in 44 B.C., Julius Caesar reestablished Carthage as a Roman city. Soon, the fertile regions of northern Tunisia imported much of empire’s grain production, and the region began to supply luxury items such as olive oil, gold, and even wild animals for the Colosseum. Cities were romanized, monuments built and mosaics commissioned by wealthy families seeking status.

The Odyssey (3rd century), Dougga. Bardo National Museum, Tunis. Photo: Dennis Jarvi

The J. Paul Getty Museum (Los Angeles), which has a program to preserve mosaics abroad, notes that “many North African Roman mosaics exhibit more vibrant colors than their Italian counterparts, a detail that has been attributed to the abundant supply of colored limestone and marble in the region.” A shift in favor towards large-scale figural compositions, such as amphitheaters and hunt scenes”. Everything can be seen in the Bardo mosaics: hunting scenes, mythological and literary events, well-known figures and everyday tasks, function both as individual works of art and parts of a greater storyline.

Virgil (3rd century). Sousse. Bardo National Museum, Tunis. Foto: Wiki

The crown jewel of the mosaic and museum collection is the only known mosaic of the Roman poet Virgil. The mosaic was discovered in a villa at Sousse and depicts the poet writing his famous epic, The Aeneid. Dressed in a white toga decorated with embroidery the poet holds on his knees, a scroll on which are written extracts from The Aeneid specifically the eighth verse Musa, mihi causa memora, quo numine laeso, quidve … He is surrounded by Clio, the muse of the history and the epic that reads a parchment, and by Melpomene, the muse of tragedy, who holds a mask. I have already mentioned right at the beginning that the word mosaic comes from muse because the Romans considered it to be such an exquisite art that they could only be the muses that inspired the artists.

The Iberian Peninsula, ancient Hispania, has bequeathed us excellent mosaics that have been unearthed over the years and set up in museums. One of the oldest was found in Cartagena, the old Carthago Nova (1st century). Today in the Museo Arqueológico Municipal of Cartagena, come from the Casa Salviu, a typical domus that decorated its floor with black and white tesserae that combine several designs around to a central motif. I recommend the visit to this small and beautiful museum designed by Spanish architect Rafael Moneo.

Caza de la pantera (4th century). Villa de las Tiendas. Museo Nacional de Arte Romano, Mérida, Spain

Rafael Moneo is also the architect who designed the Museo Nacional de Arte Romano, in Merida, a remarkable building that preserves one of the main collections of the Iberian Peninsula mosaics. The most outstanding one, which comes from the well-known Villa de las Tiendas, a country house near the city, depicts hunting scenes, including the hunting of a panther in a forest. This scene is very interesting for a medium such as mosaic, the artist has managed to capture the movement of the horse and the panther in a successful attempt to grab realism, the panther turns when she is hit by the hunter’s spear and the tree twists and fit with the fight. Made in opus tessellatum that combines glazed tesserae with colored marble tesserae, the panel is large and has been hung on a wall, in a passageway.

Mosaico del Gladiador (s.III). Museo Arqueológico Nacional, Madrid. Photo: Luis Garcia

The Museo Arqueológico Nacional of Madrid keeps fragments of mosaics from Soria, Palencia or Alcalá de Henares Roman villas, but one of the most outstanding piece is from Rome: the so-called Gladiator Mosaic made of marble and limestone tesserae in opus vermiculatum. The mosaic is divided into two panels, hung side by side on a museum wall. It shows a gladiatorial combat like in a comic strip. Interesting for moviegoers because it shows the gladiatorial fights, the combat to death, the mortal blow with the sword, scenes we have seen recreated in the “Roman” movies. It refer us, likewise, to the comic Asterix, the Gaul who defends his village and, in turn, makes fun of “these crazy Romans” who want to subdue them. These mosaics were found in 1670 in the thermal baths of a town house on Monte Celio, in Rome. Belonging to the collection of Cardinal Massimo, in 1760 they passed into the collection of the king Carlos III, who gave them to the Royal Public Library, and later, in 1867, became part of the founding collections of the Museo Arqueológico Nacional of Madrid.

(I do not know the Roman Villa of “La dehesa” in Cuevas de Soria, discovered in 1928, today part of the Magna Mater museum that, according to what I read on its website, contains more than thirty rooms of different sizes with geometric mosaic floors made with stones of different colors. I mention it for its importance and looking forward to visiting it one day.)

Mosaic de les Tres Gràcies (3rd century). Museu d’Arqueologia de Catalunya, Barcelona, Catalonia. Photo: Wiki

In Catalonia, the Museu d’Arqueologia de Catalunya, based in Barcelona, exhibits a mosaic depicting the Three Graces, on a blue background, framed by a border of curled waves. The Graces – Aglaia, Euphrosine and Talia – were daughters of Jupiter and were part of the courtship of Venus. They are usually represented as three naked young women. They were worshiped as dispensers of all that makes human life pleasant. Without them there was no joy or beauty. This mosaic is very curious not because of the subject, one of the most depicted in antiquity, but because – as far as it is known – it has hardly been represented in floor mosaics, is it because of not stepping on naked women? Likewise, as in this mosaic, the Graces are represented with the attributes of a rose and a myrtle branch in their hands, as inspiring symbols of the arts. This mosaic was discovered during some works carried out on the site of the old L’Ensenyança Convent in Barcelona, towards the end of the 19th century. Made of different colors of marble and glass, in opus tessellatum.

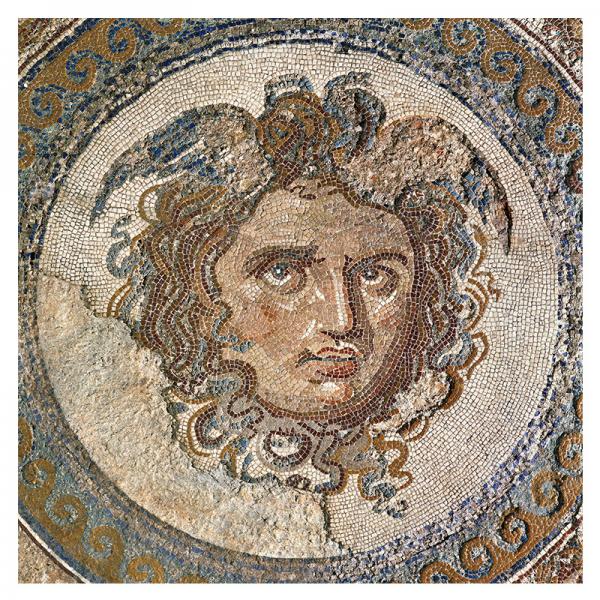

The Museu Nacional Arqueològic of Tarragona preserves a powerful Medusa made of marble, limestone, glass tesserae and sigillata ceramics, in opus vermiculatum. It was discovered in 1857 on the occasion of the works of the quarry in the port of Tarragona. Coming from the residential area of the city, it would form part of the pavement decoration of a domus. According to mythology, the Medusa’s gaze was so penetrating that anyone who looked at her turned to stone. Perseus killed her and in order not to look at her and turn him into stone he used a mirror-shield and killed her while she slept. The Medusa is a gorgon that is represented with its head surrounded by snakes. This Medusa must have been part of a large mosaic inspired by the myth of Perseus that must have been made in situ and this head would correspond to the central emblem. His gaze here is chilling.

Made in opus tessellatum and located in the museum lobby, the Mosaic dels Peixos (Fish mosaics) was the pavement of the Villa Callipolis, excavated in the town of Vila-seca in Catalonia. For lovers of the sea, it is a great source. According to the museum, the mosaic field is decorated with 47 depictions of Mediterranean marine life, mainly fish but also some crustaceans, cephalopods and mammals that it has been possible to identify. It belongs to the kind of unitary composition typical of African mosaic, in which the scene occupied the whole mosaic field, different from the tendency in the Hellenistic tradition to make small independent compositions (emblemata) delimited by geometric decorations.

As for mosaics in other European museums I highlight the mosaic from the city of Miletus (Asia Minor, present-day Turkey) on display at the Pergamon Museum in Berlin due to its great artistic quality. It have been placed in front of the famous marble Market Gate built in the city of Miletus in the 2nd century during the reign of the emperor-builder Hadrian. The mosaic was excavated in 1903 by a German team of archaeologists and took to Berlin, where in the 1920s was reconstructed in the Pergamon Museum. Following a heavy damage during World War II it underwent lengthy periods of restoration and finally reopened to the public in 2008. Orpheus was a popular subject in classical art, an important figure in Greek mythology, it was depicted in many mosaics, it was almost the star subject, and it was also used in early Christian art as a symbol of Christ. This mosaic depicts the usual Orpheus seated on a rock and playing a lyre or a cithara. He is wearing a Phrygian cap, and next to him a crow and a fox listen to him, peacefully. Orpheus has the virtue to charm and sooth animals, even the most ferocious and dangerous with his music, the humans too. As we can see in this splendid mosaic, the animals surround him and under the magical effect of his music, some are placid and others seem to dance.

Mosaic of Dionysus and the Four Seasons (2nd/3d century AD). Lugdunum Museum, Lyon, France. Photo: Romain Behar

Lugdunum, present-day Lyon, was an important city in the Roman province of Gaul because of its strategic location on a fertile agricultural plain at the convergence of the Rhône and Saône rivers. Roads led to the north, south and east. The place left an important artistic legacy that is preserved and studied at the based Lyon Lugdunum museum, devoted to the Gallo-Roman civilization. The museum is outstanding. Nearly invisible from the outside, because the architect Bernard Zehrfuss had the brilliant idea of burying the building on the slopes of Fourvière Hill next to and in front of the Roman theater and an odeon, so that it would fit smoothly into the exceptional setting around it and would not “offend the professionalism of my Roman colleagues”, affirmed the architect. The museum was inaugurated in 1975, set on the same place where the Roman city of Lugdunum was founded. The whole complex was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

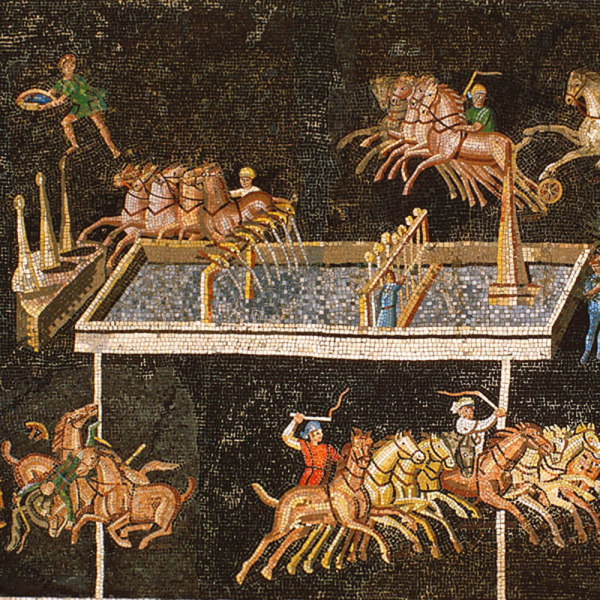

Circus Games Mosaic (2nd century). Detail. Lugdunum Museum, Lyon, France. Photo: Lugdunum

Due to the importance of the city, there were mosaics on the houses floor, some has been found and preserved at the Lugdunum. Among them the remarkable mosaic Circus Games Mosaic which depicts a great scenario with chariot races in quadrigas. The mosaic is rectangular, its scope is black, with polychrome decoration making it one of the few ancient representations of such a race. The museum web site describes as follows: “In the Roman Empire, chariot races were a major event in daily life and provided entertainment for the masses. The competing chariots were drawn by one, two, three or even six horses and were driven by aurigas. The races were held on a circus track and included seven laps, representing around seven-and-a-half kilometers. The colors worn by the aurigas corresponded to various “stables”, and spectators bet on the winners.” All the process can be seen in this mosaic, the race, the people watching, the palm leaf and a crown of laurel leaves for the winner. Made of marble and limestone, in opus tessellatum. It was discovered in 1806 in the Ainay district of Lyon buried under a meter of topsoil.

Mosaïque aux svastikas. (3rd century). Lugdunum Museum, Lyon, France. Foto: reddit

Another one is The Swastika, an immense 86-square-meter mosaic. Approximately one million tiny cubes make up this pavement, which is decorated with geometric motifs, including swastikas. This motif with an Indo-European origin was used widely in the Greco-Roman world and represents a wheel that turns, symbolizing eternal life. It is also a beneficial good luck sign, the problem was that the Nazis appropriated the symbol and turned it into an evil sign. The mosaic was made of marble and limestone, in opus tessellatum. Found in 1911 just a few hundred meters from the museum, The Swastika mosaic decorated the floor of a reception room in a vast home built on the top of the hill near a large temple.

Marine life (around 1st century). Pompeii. Museo Archeologico Nazionale, Naples, Italy. Photo: wikicommons

Other museums that I know that house large collections of mosaics are the Museo Archeologico Nazionale in Naples, which preserves those unearthed in Pompeii and Herculaneum and villas in the area; the Metropolitan Museum of Art, which has everything, The British Museum, the Louvre or the Museo Arqueológico of Seville. Anyway you can find fragments of pavement mosaics in most ancient art sections of museums around the world.

The most exciting is to see the mosaics that have been preserved in situ, to walk through the place and the surroundings for which they were designed. I have been lucky enough to be able to visit many Greco-Roman ruins throughout the Mediterranean coast over the years, the mosaics that I remember well for their beauty, historical interest and landscape are in the ruins of Itálica, in Santiponce (Seville, Spain), the villa del Casale, in Piazza Armerina (Sicily) and those of Empúries in Catalonia.

Itálica was the first Roman city founded in the Iberian Peninsula. When the Second Punic War ended, General Publio Cornelio Escipión, known by the nickname of El Africano, established an enclave on the Cerro of San Antonio and, as usual, distributed parcels in the valley of the Guadalquivir river among the soldiers of the legions that they had defeated the Carthaginians. This led to the birth of Itálica in 206 BC., in present-day Santiponce, a few kilometers from Seville. Its mosaics were discovered in 1914 under farmland and belonged to a very spacious houses of wealthy families; the mosaics are of the emperors Trajan and Hadrian period, both born in the city. The mosaics belong to a time of great prosperity, Itálica was granted the status of colony and became a small Rome with its well laid out streets, its thermal baths, a theater and an amphitheater where gladiator fights to death, all that subjects that we have seen depicted on the mosaics exhibited in the museums of Lyon and Madrid.

Neptune Mosaic (135). Itálica, Santiponce, Spain. Photo: Emilio J. Rodríguez Posada

Among the most significant mosaics is that of the Planetarium house where you can see the seven planetary divinities that give their names to the days of the week, according to the Roman calendar, associated with the stars that ruled the universe; or the Mosaic of Neptune, which depicts the polychrome figure of the god of the sea along with a complete procession of creatures in black and white, centaurs, rams, bulls and other animals that in a surrealistic drift, have been transformed into sea creatures by substituting their hindquarters by fish tails and that coexist with dolphins, fish, mollusks and crustaceans. The borders of the mosaic is decorated with Nilotic scenes. Here you can see crocodiles, a hippopotamus, a palm tree and various pygmies, hunting or fighting ibis and crocodiles. This indicates that the owner could be interested in Egypt or the Emperor Hadrian, who was fascinated by the Nile country, was able to influence since he was reigning in the year these mosaics were made. Still, interest in Egyptian subjects was not unusual at this time.

La Casa de los pájaros (The House of Birds) (2nd/3rd century) Itálica, Santiponce, Spain. Photo: Estellez/Getty Images

One of the most popular is the mosaic of birds, where 33 different species of birds are represented, each one inside a square, and that of the peacocks that takes its name from one of the mosaics on its northern side that reproduces a scene with peacocks. The site of Itálica is absolutely magnificent, very well preserved and cared for, it allows us to understand very well how a Roman city was organized, its urbanism, its buildings, its facilities and its esthetics.

Ochavada Room. Itálica Mosaics (2nd-3rd centuries). Lebrija Palace, Sevilla, Spain. Photo: PL

In order to complete the mosaics of Itálica, you must visit the Lebrija Palace, located in the heart of Seville, which with its 580 square meters of Roman mosaics, on floors and walls, make one of the most important private collection in the world. The Countess of Lebrija saw the first mosaic of Itálica in 1901, she wrote that it was in a haystack at a depth of three and a half meters, it was an octagonal mosaic, she acquired it, today can be admired in the Ochavada room of the palace. The complexity of its shape led the Countess to remodel the rooms of the palace according to the needs of each new mosaic that entered, creating, in this case, a peculiar octagonal living room because the mosaic.

Los amores de Júpiter (150). Itálica mosaics. Lebrija Palace, Sevilla, Spain. Photo: Raúl Doblado

The Lebrija Palace has more mosaics from Italica, the ones discovered in 1914 by the farmer José Ortiz. Once removed from the site, they were immediately acquired by the countess, a woman passionate about archeology. His purchase came into dispute with the authorities since 1912 the so-called ruins of Itálica had been declared a National Monument and since this date the mosaics were not allowed to pass into private hands. But the countess believed that she had the right to own them. After a long process, Doña Regla Manjón, the countess, had to return two mosaics dedicated to Bacchus, today in the Museo Arqueológico of Seville, but she was granted by Royal Order to keep the third one, Los amores de Jupiter, made of marble and limestone tesserae of various colors, in opus tessellatum. It is the one we can see at the palace courtyard. The central medallion of the mosaic alludes to Polyphemus, although some authors believe that it is Pan, here in love with the nymph Galatea, who plays a reed pipe flute. The other medallions represent love scenes from Ovid’s Metamorphoses along with the 4 seasons, it really is one of the best mosaics ever found in ancient Hispania.

Geometric mosaic (1st century). Empúries, L’Escala, Catalonia. Photo: HJPD

Empúries is a site of great natural beauty, an exceptional place where the remains of a Greek city – the colonial enclave of Empòrion – coexist with those of a Roman city, the ancient Emporiae. I remember it perfectly well, it is part of my childhood and youth, the summers on the Mediterranean coast, in the Costa Brava. Amongst stones, mosaics, statues and pines, with the intense blue of the Mediterranean Sea and the front beach, under the clear sky of the Empordà county, the strong Tramontana winds, these mosaics now in open air, were made with geometric shapes that seem current. They give us a feeling of calm, of permanence, of a cultivated and serene place, the steps of civilized Greece is noticeable. The Greek city has not left mosaics, some pavements made with mortar and ceramic, but the Roman city has left us 150 mosaics that stand out for its regular and powerful geometric shapes, its typological and technical diversity and some marine figures, birds and of flora.

Empúries means “place of commerce” and was founded in 575 BC by Greek settlers from Phocaea at the mouth of the River Fluvià, in the Bay of Roses. In 195 BC, Marco Porcio Cato installed a military camp that was the embryo of a new city, created at the beginning of the 1st century BC. After the conquest of Hispania by the Romans, Empúries remained an independent city-state until during the civil war between Pompey and Julius Caesar, Empúries sided with the former. After Pompey’s defeat Empúries was stripped of its autonomy and a colonia of Roman veterans was established near Indika (Ullastret) to control the region. In the time of Augustus the Greek and Roman parts of the city were merged and the Roman citizenship was granted to its inhabitants. In the second half of the third century, the city began to be abandoned, eclipsed by Tarraco (Tarragona) and Barcino (Barcelona) and the population moved to San Martí, which will become an important medieval enclave, while a small fishermen town will emerge close to the ancient place, L’Escala. In 1908 the Barcelona Museum Board, chaired by Enric Prat de la Riba, and thanks to the brilliant initiative of the architect Josep Puig i Cadafalch, systematically began the first acquisitions of the land where the Greek and Roman cities were located, and launched the first campaign of archaeological excavations, that have not yet stopped.

Emblem of the Sacrifice of Iphigenia (1th BC). Museu d’Empúries, L’Escala, Catalonia. Photo: Wiki

The Empúries museum exhibits the mosaic Emblem of the Sacrifice of Iphigenia that decorated the central part of one of the rooms destined for banquets (triclinia ) of a house in the Roman city that has not yet been excavated. It was found in 1849, and was made in a workshop in the eastern Mediterranean. Dating back around the 1th BC, is made of very small colored tesserae in opus vermiculatum that allow to obtain pictorial qualities. This mosaic is very important for Art History, not because it is a mosaic but because, reproduces a Greek painting, from the 4th BC, which represents the theatrical staging of the myth of the sacrifice of Iphigenia, based on the tragedy of Euripides, Iphigenia in Aulis. Due to the fact that no Greek painting has survived – only few remains-, this mosaic allows us to intuit how a Greek pictorial composition would develop.

Mosaic in Palmyra ruins, Syria. Photo: World Archeology

Another important city on the Silk Road, like Antioch, was Palmyra, the great desert oasis city, located between the Mediterranean Sea and the Euphrates River, in present-day Syria. The ruins from Roman times are spectacular and show all the splendor of what was a thriving, wealthy metropolis. It’s not really that there are many mosaics on view, but I incorporate Palmyra because only by visiting the ruins do you sense that there were mosaics everywhere, on the floors of the houses that have not been preserved and there is still much to excavate. Palmyra was part of the Roman Empire, its name means city of Palms and is known as the Pearl of the Desert. The city-state reached its peak in the late 3rd century, when it was ruled by Queen Zenobia who briefly rebelled against Rome. Zenobia failed and Palmyra was re-conquered and destroyed by Roman armies in AD 273. But its colonnaded avenues and impressive temples still stand, they were preserved thanks to the desert climate and neglect. In the 20th century Palmyra was one of the main tourist destinations to the Middle East. I visited the ruins in 2002, in peacetime, but with neighboring Iraq in conflict, during a trip to Syria with my friend Vili. There was no one in the ruins of Palmyra, just us and our guide. It was an autumn afternoon and we climbed to a small hill where the remains of a palace stand. We could see the sunset with the ruins below and the infinite desert. In Palmyra we tasted the best dates and saw beautiful oriental rugs in its little souk.

The first excavations at Palmyra were carried out in 1902 and continued throughout the last century. In 1980, the historic site was declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The city is now inaccessible because it is in a war zone. In 2015 the Islamic fundamentalist militias of the so-called Islamic State (ISIS) blew up the Temple of Baal and other structures with explosives. The Syrian Virtual Museum Project website, created to give visibility to the works of the Archaeological Museum of Palmyra, reports that hours before the attack, works from the Archaeological Museum of Palmyra were transported to Damascus to safeguard them, but it is not known which or how many were left. Palmyra’s retired antiquities chief Khaled-al Assad was beheaded by ISIS after being tortured for a month for refusing to give information about the city and its treasures to his captors. They hung his headless body from a column. During the occupation of the site, the Palmyra theater was used as the place of public executions of their opponents, they released videos showing it. Following the ISIS attack, number of Greco-Roman busts, jewelry and other objects looted from the museum have been found on the international market, it is known that they collected funds by trafficking in antiques. Anyway, the aforementioned website reports that when the Syrian government took control of Palmyra again in 2016 it seems that the damage was not as great as it was thought, with structures still standing, except the temple of Baal.

Bellerofont on the Pegasus slaying the chimera (3rd century). Palmyra, Syria. Photo: Mirath

A year after our visit to the ruins, a mosaic that is considered one of the best found recently came to light, as I read in World Archeology magazine that includes a photograph, that it seems retouched. It was discovered by the archaeologist of the University of Warsaw and director of the Palmyra site for many years, Michael Gawlilowski. One of the central panels shows the figure of Bellerophon, dressed in Persian costume, mounted on the winged horse Pegasus slaying the Chimera with a spear, with the body of a lion, the tail of a serpent and the head of a goat; drops of water come out of the horse’s hooves, since in myth the footprints of Pegasus formed springs. About the meaning of the figure Galilowski wonders: “Does this represent the Palmyrene King Odainat ,who in the 260s AD turned himself into a client king of the Romans and conquered the Sassanians, the newly emergent dynasty of the Persians who were posing a major threat to the Roman Empire?”

The half-naked lovers (4th century). Villa del Casale, Piazza Armerina, Sicily. Photo: Per-Erik Skramstad

The Villa Romana del Casale is the most renowned for its incredible mosaics. Is based near Piazza Armerina in Sicily. Built in the 4th century, the villa replaced a smaller rustic residence from the 3th century. Historians believe that a member of the Roman provincial aristocracy, possibly a governor, owned the villa and the land, it was a latifundium. In later centuries, it grew to become a large medieval settlement, until its people abandoned it in the 13th century. For centuries with frequent flooding, the mosaics remained submerged and forgotten. In the 19th century the emerging ruins began to draw the interest of scholars and foreign travellers, as well as that of antiquities dealers and amateur excavators, they started to discover the treasure trove beneath: floors that are covered almost completely with at least well preserved mosaics. There are over 50 rooms full of them, in total ca. 3500 m².

Further systematic excavation campaigns were carried out in the 20th century and the entire Villa came out, at the same time they tried solutions to protect it with iron uprights and trusses topped by sheets of plastic to cover the roof and enclosed the perimeter wall that altered the microclimatic conditions of the site with conservation consequences in terms of physical, chemical and biological equilibrium and caused serious damage to the mosaic flooring. In the 1990s, vandals attacked the site, intending to damage the villa’s valuable mosaics and frescos. Despite all UNESCO declared the Villa del Casale World Heritage Site in 1997.

The Great Hunt. Villa del Casale, Piazza Armerina, Sicily: Photo: Pinterest

The mosaics are impressive, centered around aspects of life at the time, seasons, sports, mythology, parties or hunting. The corridor called of The Great Hunt is a continuous corridor mosaic that runs 60 metres from one side of the villa to the other. The scale of this mosaic is unbelievable. It shows the capture of animals to be exhibited in circus spectacles in Rome. It is populated by a wide variety of animals, ranging from the ferocious, like lions, to the singular, like rhinoceri, to the mythological, like griffons, and peopled with soldier hunters horsemen who direct the operations and attendants responsible for the transport and loading of the wild beasts onto the ships.

The most famous, however is the subject of female athletic competitions, named the The Room of the Palestriti excavated between 1950-1960. Several women athletes are shown competing in sports that include weight-lifting, discus throwing, running, and ball-games. Much attention has been given to the competitors’ two-piece outfits, which closely resemble modern-day bikini. The mosaics probably were the work of North African craftsmen.

Marin mosaic (3rd century). Lod, Israel. Detail. Photo: Niki Davidov/Israel Antiquities Authority

Floor mosaic as an art form has nothing to do with other two-dimensional art forms such as painting and relief. On the computer screen we see them right now as if they were hanging on a wall, in vertical, but it is not that. You see them looking down and this inclination of the gaze changes all perspective, you have to design the scenes and geometric motifs to provide multiple points of view. Now, you walk around a mosaic and in the past people walked on the mosaic, so the scenes need to be oriented in different directions. As a result, Christopher S. Lightfoot, Curator of Department of Greek and Roman Art of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, points out that “figures could be depicted as floating against a minimal background, which was ideal for heavenly divinities or sea creatures.” An example is the marine panel of the Lod Mosaic found in Israel, which was on display at the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 2011: “There is therefore an overall trompe l’oeil (trick of the eye) effect in creating naturalistic patterns from unpromising materials in a most unexpected way. The most impressive examples are in the so-called vermiculatum (wormlike) technique, in which very small cubes measuring no more than 4 millimeters on each side were used. The tiny tesserae allowed very fine detail, and an approach to the illusionism of painting, entire mosaics designed to provide specific trompe l’oeil effect”. Naturally, such mosaics were very costly and so were relatively small in size. They were usually made as separate panels known as emblemata.

Lod mosaic (3rd century), Israel. Foto: Niki Davidov/Israel Antiquities Authority

The Lod mosaic is prodigious for animal lovers, it was accidentally uncovered in 1996 during the construction of a highway in the modern Israeli town of Lod, not far from Tel Aviv. Lod is ancient Lydda, which was destroyed by the Romans in A.D 66 during the Jewish War and re-founded by Hadrian as Diospolis, later, Lydda received the rank of Roman colony. The discovery of the mosaics immediately prompted a rescue excavation, undertaken by archeologist Miriam Avissar for the Israel Antiquities Authority, which revealed a series of mosaic floors that measured approximately fifty by twenty-seven feet dating back 300 AD. There are no human figures in this large mosaic, which was very unusual in a Roman mosaic with figures, here we only can see wild animals from Africa and many more mammals, as well as all kinds of fish and two boats. For its iconographic analysis it is almost better to turn to an expert in fauna than to an art historian. Animals like the giraffe and rhino are rarely depicted in ancient art, but tigers and lions are as they appeared in circuses for gladiatorial fights. Because the mosaic images have no overt religious content, experts cannot determine whether the owner was pagan, Jewish, or even Christian. However, “it is certain that he was a wealthy local resident who wished to have his home to be decorated in the finest Roman style,” it is written at Lod Archeological Center’s website. The mosaics are of exceptional quality and are in excellent condition, is regarded as the work of a master craftsman, who was highly skilled. After their discovery, the mosaic toured various museums in Europe and the United States, including the Metropolitan Museum in New York, in 2011, while in Lod the Shelby White and Leon Levy Lod Mosaic Archaeological Center, was being established. The center will host the mosaic for its preservation and visit. For more information: http://lodmosaic.org/home.html

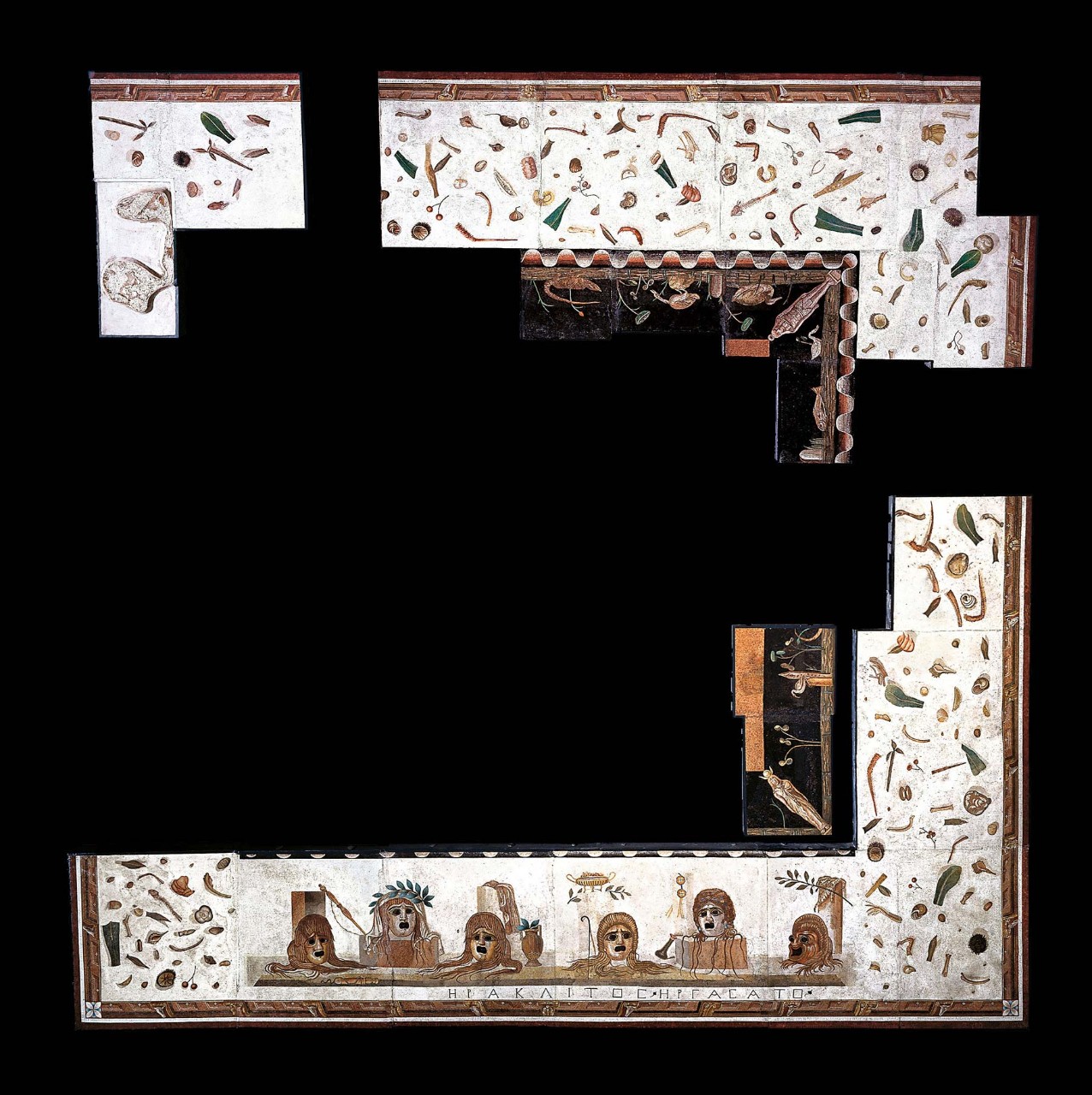

Asàrotos òikos (2nd century). Salonius House, Oudna. Bardo National Museum, Tunis

One of he most curious arrangement is the so-called Asàrotos òikos (unswept room). It is about a mosaic, boarder-like, covered the four sides of a dining room depicting, on a white background, “…the debris of a banquet, the remains that would normally be swept away.” This type of mosaic-work takes us back to the Hellenistic Period, to the city of Pergamon on the coast of Asia Minor, and to a legendary mosaicist, called Sosus, artist of the second century BC. He is the only mosaic artist whose name was recorded in literature due to Pliny the Elder who describes this Hellenistic mosaic making and Sosus’s accomplishments as follows: “…Paved floors originated among the Greeks and were skillfully embellished with a kind of paintwork until this was superseded by mosaics. In this latter field the most famous exponent was Sosus, who at Pergamum laid the floor of what is known in Greek as ‘the Unswept Room’ because, by means of small cubes tinted in various shades, he represented on the floor refuse from the dinner table and other sweepings, malting them appear as if they had been left there…” Pliny, Natural History, 36.60.25

The Gregoriano Profano Museum, at the Vatican, shows one of them, the splendid mosaic, made up of tiny pieces of glass and colored marble once decorated the floor of the dining room of a villa on the Aventine Hill in Rome. It was discovered in 1833, and as the archaeologists established, it decorated the dining room floor of a Hadrian period villa. This is a unique mosaic, the masterpiece signed by the mosaicist Heraklitos, the artist’s skill demonstrates an understanding of three-dimentionality. Let’s read the museum explanation: “The artist has created a floor which seems to be covered with the debris of a banquet, the remains that would normally be swept away: one can identify fruit, lobster claws, chicken bones, shellfish and even a tiny mouse who is gnawing a walnut shell. The solidity of the objects shown has been created by a clever use of colour to create shadows against the white background of the floor. Where the room would originally have had an entrance there is a design with theatrical masks and ritual objects; at the centre there is part of a complex Nile scene.”

Doves (2nd century). Sosus’s copy. Capitoline Museums, Rome. Photo: Cambridge University Press

Nothing remains of Sosus, only what appears to be a copy, a mosaic found in Hadrian’s Villa, now in the Capitoline Museums, depicts a group of doves and one of them drinks from a bowl. They are depicted very realistically. The mosaic is made only of cubes of colored marble, without any colored glass as in other mosaics. It was discovered in 1737 during excavations at Hadrian’s Villa led by Cardinal Giuseppe Alessandro Furietti, who thought it was the mosaic that Pliny had described, although other scholars think it is a copy of the original that was made for Hadrian.

Roman mosaic (4th-3rd century). Uzès, France

Mosaics placed on a floor were ideal for making repetitive geometric patterns. Early pebble mosaics were often based on a simple checkerboard pattern of alternating black and white squares, but in Roman times there developed an extensive repertory of non-figural designs incorporating geometric and floral patterns. Some are very intricate and elaborate, they can even look like mazes. Often they served as borders for the main figure scenes. Others are whole grids, interlaced with rhombuses, frets, waves, triangles, squares, dots, etc. in black and white or made of marble in contrasting colors that can give the impression of a three-dimensional space.

Christian Mosaics

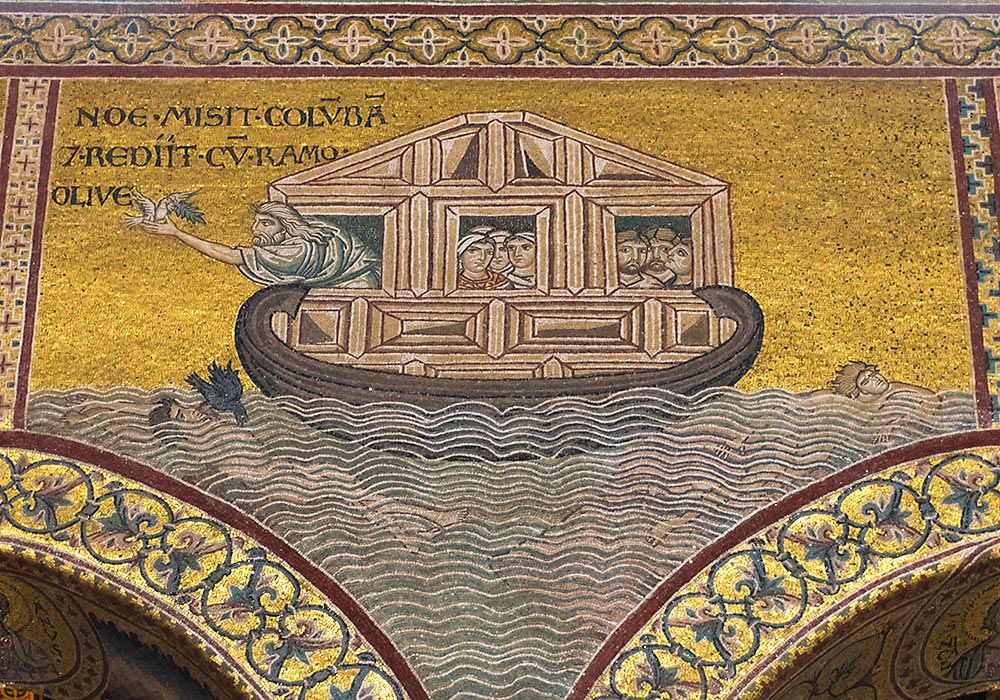

Scene from the old testament (12th-13th centuries). Cathedral of Monreale, Sicily. Photo: Per-Erik Skramstad

This Roman legacy in mosaic art was taken over by early Christians and displayed by their artists and craftsmen in splendid mosaics, particularly later in Byzantium. Mosaics will be moved from the pavement to the walls, vault and domes, replacing a large extent the older and cheaper technique of mural painting. However, the earliest use of mosaics in a vertical position for wall decoration found are at Pompeii, but only appears in niches. It was really only after the adoption of Christianity as the official faith that the possibility of mosaic covering for walls or vaults came to be fully exploited. And in Byzantine times there is a substantial change: the tesserae won’t be carved in marble or terracotta but in colored glass which offered colors of far greater range and intensity than marble tesserae, including gold, even if lacked the fine gradations in tone necessary for imitating painted pictures. According to Art Historian H.W Janson: “Moreover, the shiny (and slightly irregular) faces of glass tesserae act as tiny reflectors, so that the over-all effect is that of a glittering, immaterial screen rather than of a solid, continuous surface. All these qualities made glass mosaic the ideal complement of the new architectural aesthetic that confronts us in Early Christian and Byzantine basilicas.” So, the monumental mosaic is perhaps the most original medium of Early Christian and Byzantine art.

Mausoleum of the Julii (3rd century.) Detail. Saint Peter, Vatican City. Photo: Wikipedia

According to John Gage, the decisive break with the methods of pavement mosaics probably came with the introduction of metallic tesserae – first gold, then silver. In the vault mosaic of the Mausoleum of the Julii, under St Peter’s, in Vatican City, the analogy gold-light is overt, since Christ here appears as the nimbed Helios Roman sol invictus with an aureole riding in his chariot, within a framing of rinceau of vine leaves. This tomb was first discovered in 1574 when workmen accidentally broke through the ceiling while conducting some floor alterations in the basilica. So, the use of metallic tesserae is the first clear indication that the Early Christian and Byzantine mosaic was to be primarily a vehicle of light. Don’t forget that Christian believe that God is light, glass and gold can simulated divine light.

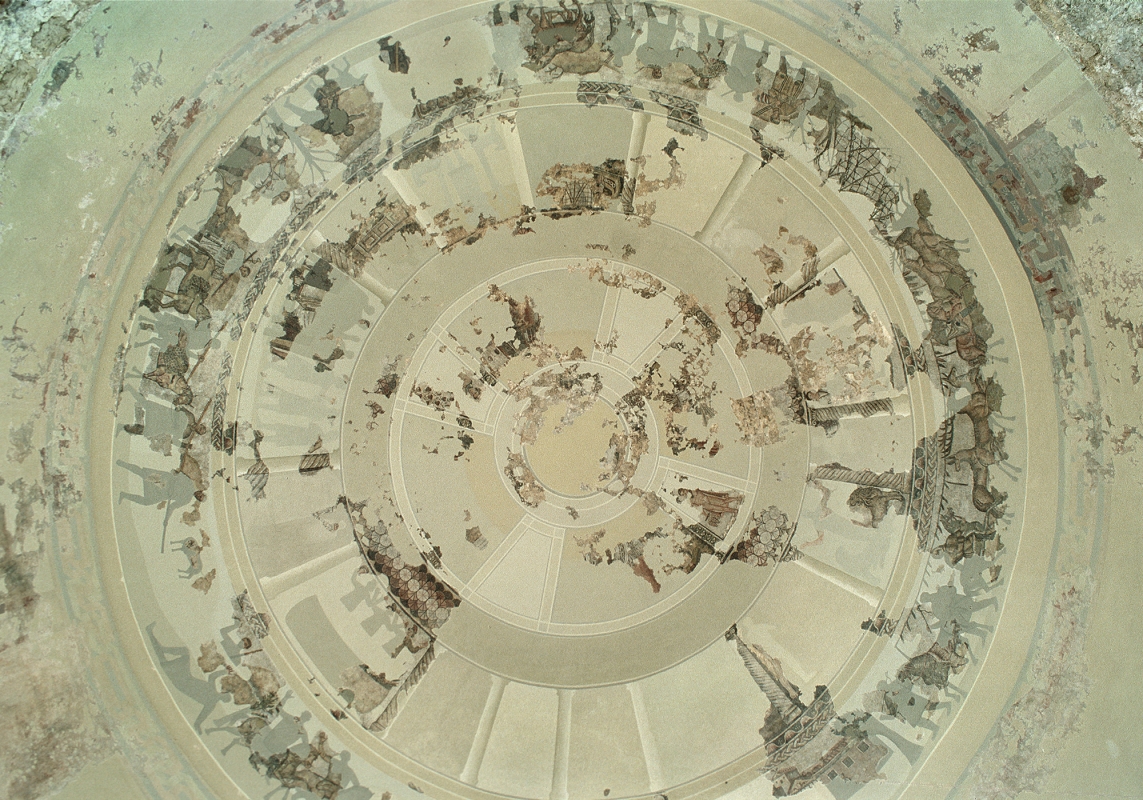

Centcelles mosaics (4th century). Detail. Constantí, Catalonia. Photo: MNAT

The first Early Christians mosaic began to be placed at the apses and a little bit later they were placed too on vaults and domes. The mosaics found in Centecelles, in Constantí (Catalonia) are considered to be one of the oldest Christian-themed dome mosaics of the Roman world, 4th century, although they are very fragmented, they are well preserved. They are in a closed circular room with dome of a magnificent Roman Villa. The mosaics represent several scenes, organized into three areas: a hunt on the lower section, biblical scenes from the Old and the New Testament in the central part and figures of the four seasons at the top.

Centcelles mosaics (4th century) Constantí, Catalonia. Photo: MNAT

They were set up in a circular domed room of a large Roman villa that might be owned by a notable person in the ecclesiastical or civil hierarchy, some scholars thinks that might be a mausoleum. Really we don’t know. In the Middle Ages, the building of the Villa were converted into the church for the town of Centcelles, which was abandoned in the 14th century. In the 19th century, the monument passed into private hands and turned it into a farmhouse. The dome room was divided into three floors. In 1959, the German Archaeological Institute of Madrid purchased the building and began archaeological excavations, as well as major restoration and consolidation on the dome mosaics. A respectful restoration has been done, without adding any new tesseare and only hinting as if the missing figures were shadows. In 1978, the complex was ceded to the Ministry of Culture of Spain and open to the public and now depends on the Museu Nacional Arqueològic of Tarragona, Catalonia.

The soldier martyrs Basiliskos and Priskos (5th century). The Rotunda (St. Georges church), Thessaloniki, Greece. Photo: Bente Kiilerich

By the fifth century whole wall faces were also being adorned. English archeologist and Art Historian of the Edinburg University, David Talbot Rice, wrote: “A large series of scenes could be set up on the flat wall surfaces, and as time went on these scenes tended to become a more and more important part of the church decoration. It was there that the Bible story was unfolded for the faithful to follow, while the more sacred figures of the Christian story were placed above, on the vaults or later, in the domes. It became the custom to adorn all the richer churches in this way; in the poorer ones paintings took the place of mosaics.”

In the beginnings of Christianity, religion and its practice were persecuted, so in during this periods there had been no need, and indeed no possibility, of building public places of worship. Everything was done secretly, in catacombs, and what still cannot be called a church were small and discreet enclosures. In the year 311 all changed. In the Edict of Milan, Constantine was the first emperor to stop the persecution of Christians and give Christianity freedom of worship along with all other religions in the Roman Empire, with which they coexisted for at least another century. Gradually Christianity creates its own structures and becomes a church as a established power in the State. In the year 380, with the Edict of Thessalonica, Emperor Theodosius proclaims Nicene Christianity as the official religion of the Empire.

As Art Historian E.H Gombrich points out, “once the church had become the greatest power in the realm, its whole relationship to art had to be reconsidered. The places of worship could no be modeled on the ancient temples, for their function was entirely different. They need a space. The new church has to find a room for the whole congregation that assembled for service when the priest read Mass at the high altar, or delivered his sermon.” That’s means altars and objects such as chalices, patens, crosses, etc. were needed for the celebration of Mass. In addition, they had to make visible images of Christ, the Virgin, the saints and episodes of the Gospels or illustrating particular scenes of the Bible in order to maintain the faith of the faithful. Thus it came about that churches were not modeled on pagan temples, but on the type of large assembly halls which had been known in classical times under the name of basilicas, which means roughly “royal halls”.

Virgin Hodegetria (11th century). Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta, Torcello (Venice), Italy. Photo: David Lown

And these great basilicas and churches, in the Byzantine world, from the 5th century onwards were entirely covered with mosaics: “Where the space was to small for figures or scenes, lovely decorative patterns were set. Every advantage was taken of the architectural frame afforded by the building, for the numerous semi-domes, niches, and curves of Byzantine architecture afforded admirable opportunity for the scintillating lights and colors of the material to play a full part; for, though admirable enough on a flat wall as we see at Ravenna, mosaics have an additional beauty when set on a curved surface. In such a position the cubes take up and reflect the light with an effect that is ever changing and which in itself alone is of the rarest beauty. No more appropriate place for Christ could be devised than the Dome nor for the Virgin than the conch of the apse”, specified David Talbot.

The Last Judgement (12th century). Detail. Cathedral of Santa Maria Assunta, Torcello (Venice), Italy. Photo: Monica Cesarato

The mosaics of Santa Maria Assunta, on the island of Torcello in the Venetian lagoon, reflect the meaning of this new artistic medium that was consolidated and magnified the following centuries: the impressive Virgin Hodegetria, with the child standing in a blue robe against an empty apse of gold, in the lower level the eleven of the apostles and Saint Paul; and the monumental mosaic on the wall The last judgment.

Pope Gregory the Great, who lived at the end of the sixth century sentenced: “Painting can do for the illiterate what writing for those who can read”. So, according to Gombrich: “It was of immense importance for the history of art that such a great authority had come out in favour of painting.” So, Christian images must be represented in order “that many members of the Church could neither read nor write, and that, for the purpose of teaching them, these images were as useful as the pictures in a picture-book are for children.”

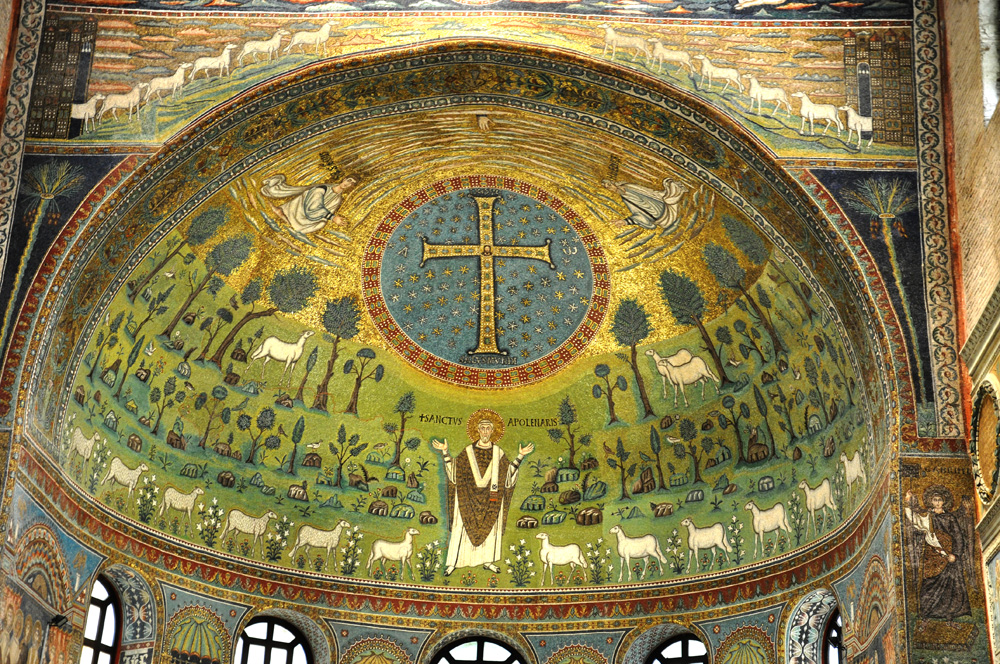

The Miracle of the Loaves and Fishes (520). Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna, Italy. Photo: Richard Stracke

But what has changed is the style, these images are no longer narrative but symbolic. Gombrich puts the example of S. Apollinare in Classe basilica, based in Ravenna. Its mosaics illustrate the story from the Gospels in which Christ fed five thousand people on five loaves and two fishes: “An Hellenistic or a Roman artist have seized the opportunity to portray a large crowd of people in a gay and dramatic scene. But this master choose a very different method. His work is not a painting done with deft strokes of the brush, its a mosaic laboriously put together, of stone or glass cubes which yield deep, full colors and give to the church interior, covered whit such mosaics, and appearance of solemn splendor. The way in which the story is told shows the spectator that something miraculous and sacred is happening. The background is laid out with fragments of golden glass on his gold background no natural or realistic scene is enacted. At first glance, such a picture looks rather stiff and rigid, and yet the artist must have been very well acquainted with Greek Art. He knew exactly how to drape a cloak round a body so that the main joints should remain visible through the folds. He knew how to mix stones of differing shades in his mosaic to convey the colors of flesh or of the rocks.”

Three Magi (566). Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna, Italy. Photo: Deagostini/Getty images

Mural mosaic was a luxury medium; the examples which we now know were for the most part of imperial or papal patronage in churches. The gold glass tesserae gave ostentation, shine and look like precious stones. Ancient Egyptian artisans already used glass to simulate gems. Emperor Justinian and Empress Theodora appears in the San Vitale mosaics in Ravenna with jewelry and lavish dresses. In Sant’Apollinare Nuevo mosaics the Persian costumes of the Three Maggi caught later the attention of painters and were widely imitated even by the kings of the popular parades in Spain and Catalonia of the Maggi Kings on present day.

Christ Pantocrator (6th century). Basilica of Sant’ Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna, Italy. Photo: Bob Atchinson

The Byzantine art expert Bob Atchinson remarks the figure of the Pantocrator of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo and its splendid colors: “Here we’ve got a Christ with purple hair. The artist who made his mosaic took the imperial purple color of the robe and used for His curls. This purple is the true imperial purple that was made from murex shells. Of course, this mosaic is made of glass cubes. In later times the Byzantines created a substitute for murex dye that was a dark red. No one except the Emperor was allowed to wear it.” The cubes of the face, even the red ones are made of different shades of marble and limestone. Atchinson explains that mosaic workers often divided their work with the top artists with the most experience doing the most important figures entirely – like Christ. Less talented artists or apprentices did clothing and the faces of less important figures.

The Virgin Martyrs. (6th century). Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna, Italy. Photo: Bob Atchinson

On the walls of the central nave of S. Apollinare Nuovo, above the arches, in a row there are 22 figures of Virgin Martyrs on one side, and 26 men, saints, prophets and evangelists on the other. There are fewer women because their procession ends with the famous three figures of the Magi delivering gifts to Christ and his mother. We contemplate them from below and looking up it seems that all the figures look alike. It’s not that. The Ravenna mosacicists were never simple copyists, they always experimented with new trends, poses, and techniques that they incorporated into their work. The martyrs wear celestial crowns of martyrdom, but each Virgin has her own inscription that identifies her, different hair color and coiffure, as well as clothing and jewelry have different designs, even some have their hands covered while others uncovered.

The Saints (6th century). Basilica of Sant’Apollinare Nuovo, Ravenna, Italy. Photo: Bob Atchinson

Men wear halo, many of them have gray hair and other are beards or are beardless. The figures are executed in a Hellenistic-Roman tradition and show a certain individuality of expression. Each individual depicted holds a book, in either scroll or codex format. They all wear white tunics made of three shades of white marble and limestone cubes and each of their robes has a mark or symbol in it. The gold background is studded with red terracotta cubes. This was intentional and toned down and made the background look less garish. The skills of the craftsmen were exceptional, they knew perfectly how to create effects and at the same time maintain a harmony of colors and rhythm. This mosaic was made in the time of Theodoric.

Anyway, John Gage has analyzed that within the mosaic materials themselves there was a hierarchy of values from marble to glass and finally to stone or terracotta cubes: when the more valuable ran out, mosaicists sometimes had to make with the cheaper. Sometimes the backgrounds were made of mosaics while the faces were painted, such as the Pantocrator of the Monreale Cathedral, en Sicily. The tesserae that simulated gold were the most appreciated and as already has been mentioned, gold is a divine symbol. The gold and silver tesserae went through a complicated manufacturing process: first, glass plates were made, on which the metallic, gold or silver plate, obtained after working the metal by hand, was applied. On the metal plate was placed a very thin sheet of glass, called cartellina, barely 1 mm. thick, whose objective was to protect the surface of the metal. They were then put into the furnace, where the glass melted and surrounded the metal plate. The Monreale mosaics were made of 2,200 Kg. of pure gold, experts estimate. Artisans from Constantinople and Venice were hired to speed up the work, almost all the walls of the cathedral are lined with mosaics. It is dazzling.

Pantocrator (12 th century). Cathedral of Cefalú, Sicily

Sometimes, skilled artisans set the tesserae in a controlled irregular surface created by raking some metallic tesserae downward at an angle of up 30o, so as to reflect light down to the spectator below. We experience it watching the mosaics at the Monreale and Cefalú Cathedrals, both have a very similar decorative schemes, and both have been declared World Heritage Site by the UNESCO. The mosaics shine due to the extensive use of glass mosaic and emit light. These mosaics with gold dazzle, achieve sumptuous effects, in my eyes, too much, but it can be understood in another sense: as has already been said, gold symbolizes divine light. The Pantocrator of Cefalù, in his left hand carries the Gospel of John, in which it can be read, in Greek and Latin: “I am the light of the world, whoever follows me will not wander in darkness, but will have light of the life”. These cathedrals unite what seems impossible: asceticism and lavishness. Bob Atchinson points out that four colors of blue glass have been used in the Christ of Cefalú robe, the artist has done an excellent job in modeling the tunic by increasing the number of folds which are drawn in black glass cubes. The shades of blue have different glossiness which reflects light in different ways with more sparkle. These mosaics were made by a contracted workshop in Constantinople associated with projects of the imperial court; arrived via merchant ships to Palermo. The mosaics were thought as a votive offering to Christ for the victory of the forces of Roger II in their attack on Manuel I and Byzantium in 1148. The great seraphim of the vaults are a replica of those in the south gallery of Santa Sofia, in Istanbul.

Following this line, John Gage believes it was through mosaic that the artists of the early early Christian and Byzantine churches were able to convey their message of salvation: “They achieved an astonishing degree of expressiveness in this difficult medium, in which bright colors, including gold, were fused into little glass cubes, the tesserae, giving an enhanced brilliance and by varying the angles of their surfaces, creating sparkle and shimmer as the spectator moved. Tesserae might be a set at an angle at strategic places, such as haloes, to reflect light downward, or optical techniques could be used to create a variety of effects. Flesh was warmed by a random scattering of red tesserae, for example, or a chequeboard type of shading gave an optical shimmer to soft or lustrous subjects. The examples range from the fifth to the fourteenth century”.

Mausoleum of Gala Placidia (430). Ravenna, Italy. Photo: Italy Magazine

I am attracted by the representation of starry skies as the one of the Galla Placidia Mausoleum, in Ravenna, a small cruciform building put up as a funerary space for the powerful Galla Placidia, daughter of the Roman Emperor Theodosius I. The interior is covered with mosaics dominated by deep blue tesserae interspersed with flowers, stars and wheels, giving it a evocative and magical atmosphere to the architectural space. The dome host 900 golden stars in a deep blue sky, with a cross in the center symbolizing the resurrection. The scenes in the mausoleum represent the victory of life over death. Declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO, it has been described as “the oldest monument with the best preserved mosaics and, at the same time, one of the most artistically perfect”. The decoration is one of the most complete and most successful that survives from early times. The mausoleum is reputed to have inspired American songwriter Cole Porter to compose Night and Day while on a 1920s visit. We can admire another starry skies at the Albenga Baptistery, Liguria, and in St Cosme and Damian in Rome. These starry skies would be understood as entering in a realm of light that comes from heaven that in medieval times will reach its zenith in the Gothic cathedrals with their stained glass windows.

The basilicas of Ravenna, the Basilica of Santa Sofia, in Istanbul (mosque since 2020 by order of the Turkish government), the Cathedral of Monreale, in Sicily, and especially the Basilica of San Marco, in Venice and Santa Maria in Trastevere in Rome, of the ones I know, still offer the most authentic experience of a Byzantine church, the most genuine. They are buildings that have hardly undergone modifications. Even so, you have to make an effort of imagination. Now we visit them with electric lights that provide an uniform brightness, but at that time the images were seen through candles and with little natural light. The light was flickering, lights and shadows fluttering… the images trembled, like specters emerging from the walls or vaults, while now with the uniform light we can see them hieratic, substantial, immobile. The sensation had to go from the terrifying to having the conviction of being in a sacred space with all that it means.

Mosaic Byzantine periods and style

Pantocrator (4th century). San Vitale, Ravenna, Italy. Photo: Bob Atchinson

As for the style, the Byzantine mosaic can be divided, generalizing (the specialists make more subdivisions in Ravenna) into two groups: one that follows the classical Hellenistic tradition, seeking verisimilitude, more naturalistic, a smaller stone tesserae was used to model the flesh and a more linear assembly method was widely executed in Constantinople. The followst the predominant Byzantine style with its hieratic figures. The Basilica of San Vitale in Ravenna is very interesting because it offers us both styles. The Christ in the apse, holding the parchment of the seven seals, is a beardless youthful figure typical of classical art, while the groups of portraits of Justinian and Theodora are completely Byzantineized and owe a greater debt to Eastern heritage than to the Roman. However, the portrait of Justinian despite his hieraticism, has verosimilitude. Maybe because was taken from life in Constantinople and sent to Ravenna where it was inserted into the plaster as a part of a large procession of him along with military officers and high-church officials that were added by local mosaic artists.

As for the periods, David Tabot Rice has divided Byzantine mosaics into two great periods: the first, from the 4th to the 7th century, Rome, Ravenna and Thessaloniki were the most important centers, or rather, it is in those cities where they survive at present the main mosaics of the first centuries. The second goes from the 9th to the 12th century, but even until the 15th century, beautiful mosaics were made, to this period correspond those of San Marco in Venice or the Cathedral of Monreale in Sicily or the Church of Daphne in Greece, to put the examples I know of.

Both periods are separated by the iconoclast age, where the representation of human figures were banned. Emperor Leo III, the Isaurius, in the Eastern Empire, in the year 726, with the advice of Muslim collaborators, contrary to the representation of the human figure, imposed his opposition to the images and decreed the destruction of all representations of Christ, the Virgin and the Saints, in a systematic removal of paintings, reliefs, mosaics, sculptures from churches and destruction of illuminated manuscripts. They promulgated that only the Christian symbol, the simple representation of the cross or decorations with leaf designs, should be used on the walls of the churches and in the manuscripts. Almost all early Byzantine art in Constantinople was destroyed during the iconoclastic devastation that rocked the Roman Empire in the East from 726 to 843.

Fortunately, the monastery of Saint Catherine, located at the foot of Mount Sinai, a walled fortress from the 6th century, was able to preserve most of the great Byzantine icons and mosaics. Its remote location allowed it to escape devastation during the two centuries of iconoclastic fury. I read in an article by José Ángel Pedraza that the so-called Transfiguration Mosaic, which is in the apse, has just been restored. He reports that it is made up of more than half a million glass, gold and silver tesserae and stone tiles were used for the reddish tones, with a range that goes from pinkish white to orange: “Most of the mosaic are made up of glass since, due to their low weight, they allowed to cover large wall surfaces without the danger of overloading the structure. Their brightness and the refraction of light gave great vibrancy to the design, which changed from time to time throughout the day, depending on the light it received. In total, there are glass tiles of more than 30 different shades, used mainly in the largest figures.”

While iconoclasm was devastating for the Christian mosaic, it was not for the Muslim where human figures are not depicted and therefore escaped of destruction.

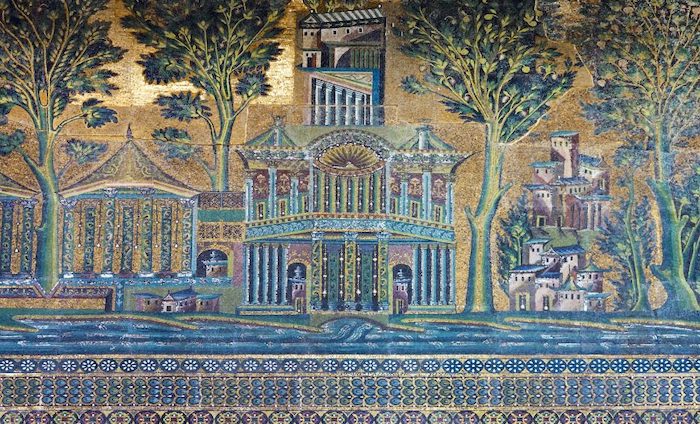

Great Mosque of Damascus (714/15). Syria. Photo: Erik Shin

The mosaics of the Umayyad Mosque of Damascus, the Great Mosque, built by the caliph al Walid in 715 shows a high degree of beauty and perfection, one of the most impressive I have seen in my life. Before the civil war that rages in Syria, when we visited the mosque, the courtyard functioned as a social space for the inhabitants of the bustling city of Damascus, friends, families, children chasing each other through the colonnade and some tourists wandering around. In free hours of prayer, we could go inside, with a guide. The mosaics are outside, although a fire in the 1890s severely damaged the courtyard and interior, much of the mosaics survived. The most important mosaics that can be seen today were first uncovered in 1929, when the plaster covering them -applied by the Ottomans- began to be removed. I read in the Qantara Mediterranean Heritage web site that the repairs carried out on the mosaics over the centuries altered their original appearance very little. However, the 20th century restorations were not always undertaken with great scientific rigour: “In places, large blanks were covered in a more or less felicitous imitation of Umayyad mosaics. These restorations are generally easy to identify because of the dividing lines if not by their style and colour, often different from the older mosaics.” Despite all, David Talbot Rice recognize that in “the churches of the Byzantine world nothing so elaborate has survived, the religion of the age being extremely severe and restrained.”

Barada Mosaics. Great Mosque of Damascus (8th century). Syria. Photo: american rugbier

The decoration essentially is based in a number of huge compositions made up of trees and buildings with its architectural elements: colonnades, archs, towers, balconies, and niches rise up. Vine and acanthus plants twist round the columns, trees spring form the river banks. The subjects stand out against a golden background and the predominating colours are blue and green. Elaborate shading in darker tones serves to accentuate at the same time the naturalism and the fantasy of this lovely compositions. The most spectacular panel is known as the Barada because the river shown all along this mosaic is often identified as the one that crosses Damascus is very large. It is located at the western portico. The towns are formed of various architectural elements assembled, many varieties of trees stand between them. The architecture and the plants depicted have clear origins in the artistic traditions of the Mediterranean. For instance, acanthus-like scrolls not only are they similar to those found in the Dome of the Rock in Jerusalem, but similar to Roman.

Mosaic, Great Mosque of Damascus (8th century). Syria. Photo: Britannica

Scholars traditionally attributed the creation of these mosaics to artisans from Constantinople, traiend in the Byzantne style, because a twelfth-century text claimed that the Byzantine emperor had sent mosaicists to Damascus. Besides, according to Qantara, “the style of the Damascus mosaics and their repertory of ornamental forms as well as the images of landscapes are clearly based on Byzantine and late classical models.” However, recent scholarship has challenged this as the text that made this claim was written from a Christian perspective and is much later than the mosaics. Scholars now think that the mosaics were either created by local artisans, or possibly by Egyptian artisans (since Egypt also has a long tradition of decorating domes with mosaics). Anyway, there is a striking difference: The absence of human figures and which implies of course the absence of narrative scenes. This is one of the first examples of the application of the Islamic ban on the representation of animate creatures. Here it should be remembered that this ban concerned sacred art, profane art being mainly figurative. Several hypotheses have been put forward to interpret this decoration, which may consist of images of paradise, based on an interpretation of Quranic verse , although in Byzantine mosaics we have seen this type of vegetation supporting religious figures.

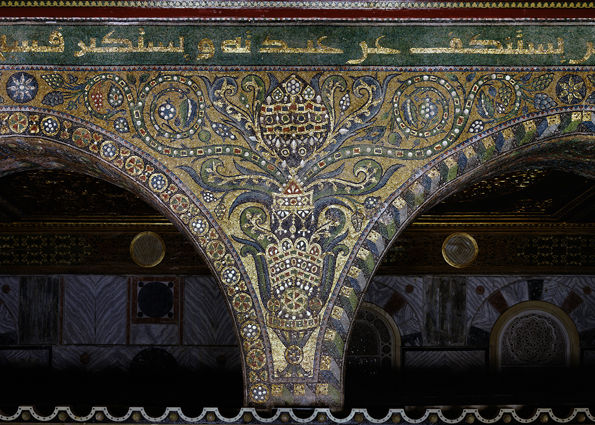

Another lovely Muslim mosaics that I have seen are in the Dome of the Rock (691-92), also known as the Al Aqsa mosque, in Jerusalem. The building is lavishly decorated with mosaic, faience and marble, much of which was added several centuries after its completion. It also contains Qur’anic inscriptions. Originally constructed between 688 and 692 under the rule of Abd al-Malik, the Dome of the Rock/Al Aqsa is one of the most emblematic architectural landmarks in the history of Islamic culture. The building is locaed on top of the Temple Mount (the site of Solomon’s and Herod’s Temples) in Jerusalem, framing a rock that holds sacred significance for all three monotheistic religions. In the Judeo-Christian tradition this rock marks the place where Abraham came to sacrifice Isaac; for Muslims, it came to be thought of as the site of the miraj, the Prophet Muhammad’s miraculous ascension to heaven with the angel Gabriel and his faithful horse Buraq. The Dome of the Rock/Al Aqsa has historically functioned—and continues to serve—not as a mosque but as a shrine, and one of the most important sites of pilgrimage for Muslims worldwide. The golden dome, the building and the esplanade, all above the Wailing Wall, what remains of the Temple of Solomon; is in this place where you understand and clearly perceive the unsolvable problems of the area.

Dome of the Rock/Al Aqsa mosque mosaics (692). Jerusalem, Israel. Foto: Said Nuseibeh

According to Ana Botchkareva, curator of the Department of Islamic Art at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, the Dome of the Rock/Al Aqsa is a perfect example of Islamic interaction with Byzantine artistic and architectural traditions: “The overall form of the architectural dome follows the Byzantine model of churches and martyriums (structures designed to house relics); and the mosaics decorating its interior draw extensively on Byzantine mosaic techniques and aesthetics in their execution of vegetal motifs (while combining them with Sasanian iconographic elements). Thus, although the Quranic inscriptions adorning the Dome of the Rock promote the virtues of the Islamic faith over Christianity, the architectural and decorative programs are heavily indebted to the Byzantine Christian artistic tradition, which they recombine and reinterpret to create a triumphal message.”

Monastery of Daphni (1100), Greece. Photo: Bob Atchinson

Back to Byzantium, the second period from the 9th to the 14th century, in the Post-iconoclast age, was in many ways the most important for the production of mosaic decorations on a full scale. Embrace a wider geography. David Talbot Rice points out: “The work was done by Byzantine as well as by native craftsmen in Russia, and western Asia minor, Greece and the Balkans were well-nigh as important as Constantinople itself. Work of the age was invariably characterized by a new, very sublime, grandeur, and by an essentially transcendental approach. There was an ethereal elongation of the proportions of the human figure and the fullest advantage was taken of the nature of the building to produce a moving, at times almost an awesome, effect”, pointed out David Talbot Rice. For him the mosaics of the Daphni monastery (1100), near Athens, constitute what is perhaps the most perfect monument of the age. Mosaics remained popular until the Empire became so impoverished that patrons were no longer able to sustain the immense expense of furnishing a mosaic decoration for a whole building.