L’artista viurà per sempre!, va afirmar el pintor i un dels millors dibuixants de tots els temps, l’austríac Egon Schile (1890-1918). No, els artistes no viuran per sempre, però, les seves obres sí. No obstant això, el problema és quan els artistes moren joves, com li va passar a Schiele, als 28 anys. Quina pena. És inevitable preguntar-se com hauria evolucionat la seva obra, quina vida hauria portat aquest home que la va viure tan intensament i tan curta, un home tan fràgil i tant segur de si mateix alhora. Boig o massa lúcid, controvertit sempre. (Imatge superior: Self-Portrait with Chinese Lantern Plant (1912). Leopold Museum, Viena)

Els herois moren joves, ens diu la mitologia, perquè són persones que han realitzat les seves gestes més enllà dels límits humans, ho han donat tot massa aviat, sense pauses i sense descans. És un punt de vista romàntic? Al llarg de la història de la pintura, els pintors que han mort massa aviat ha estat per mala salut, per contreure malalties que llavors no es podien curar, guerres, mals hàbits o simplement mala sort. Toulouse Lautrec, Van Gogh, Raphael i Hishida Shunso van morir als 37, Modigliani, Franz Marc i Moira Dryer, als 36, Robert Smithson als 35, Umberto Boccioni als 34, Giorgione als 33, George Seurat i Keith Haring als 32, Jean Michel Basquiat als 28, Aubrey Breadsley als 26.

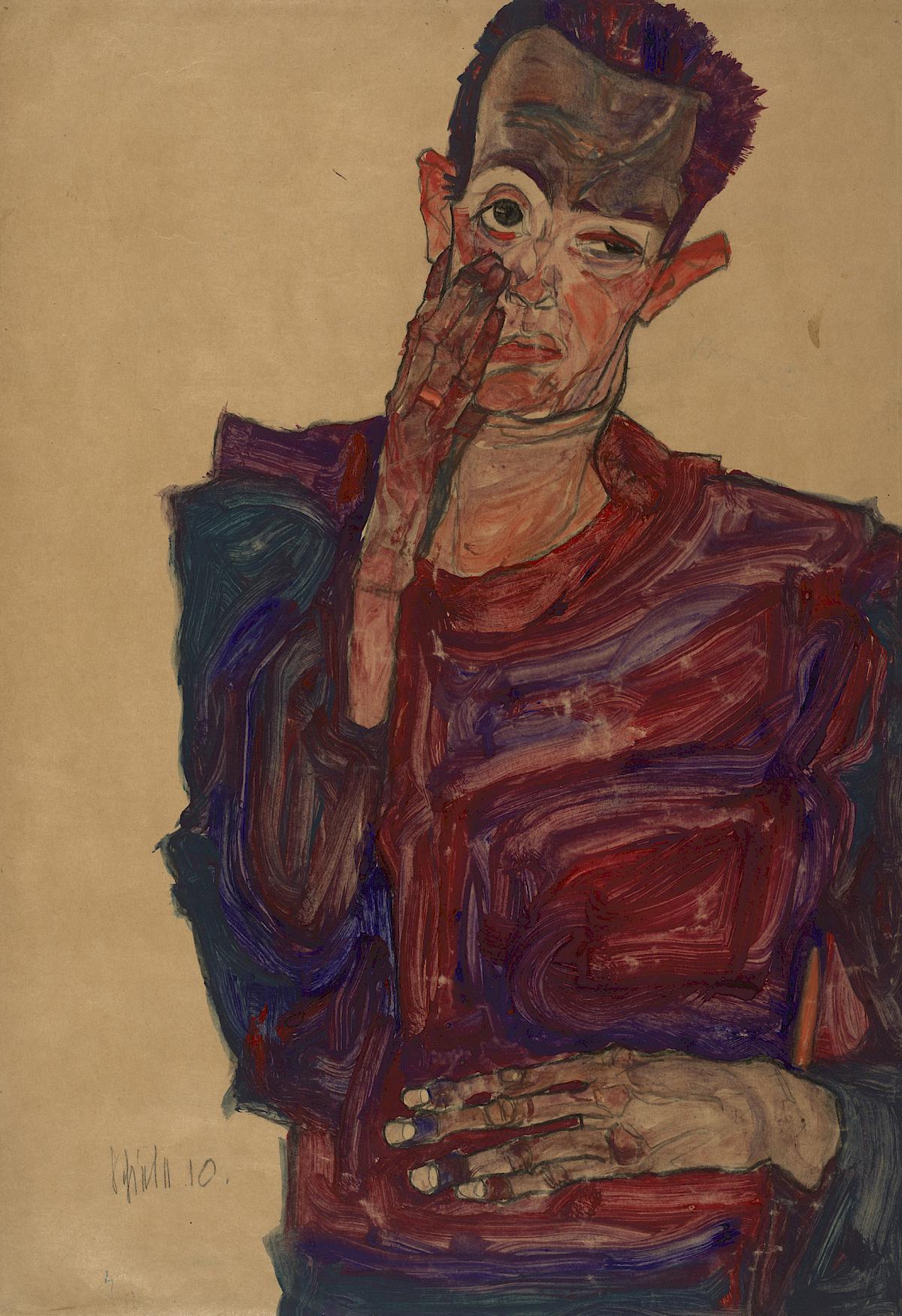

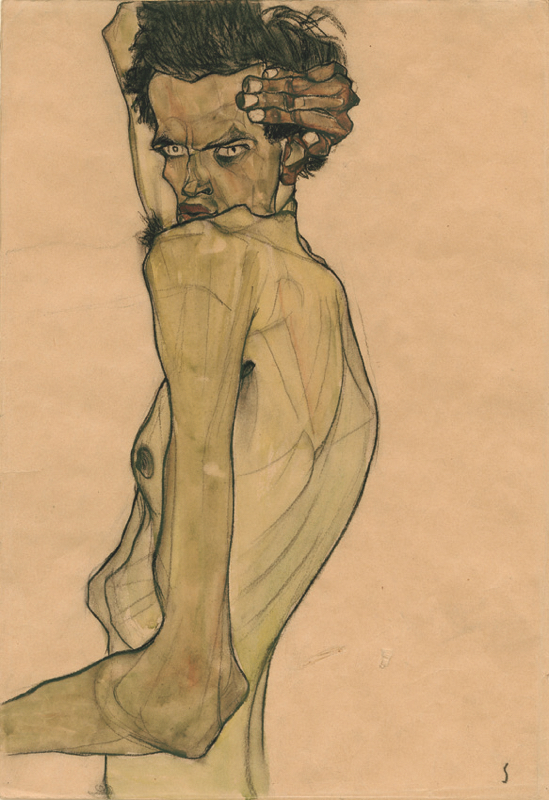

Egon Schiele. Self-Portrait pulling down an eyelid (1910). The Albertina Museum, Viena. Foto: AB

Per si serveix de consol, Schiele va afirmar:

Una sola obra d’art vivent serà suficient per fer immortal a un artista.

Qualsevol dels seus extraordinaris dibuixos ho ratifica, tot el conjunt de la seva pertorbadora obra que no deixa indiferent a ningú. Schiele va morir el 1918 a causa d’una epidèmia, l’anomenada grip espanyola, que va matar a tanta gent com la 1a Guerra Mundial, després d’una vida suposadament excessiva i que en el moment de la seva mort es trobava en un punt dolç, a punt de ser pare i jove pintor reconegut, el membre més prometedor de la Secessió vienesa després de la mort de Gustav Klimt uns mesos abans que ell. Egon Schiele va viure en els anys del canvi de segle, del XIX al XX, en un àmbit artístic entre l’anomenada decadència de fin de siècle a Viena i les avantguardes europees. Estudiem la seva pintura en el marc de la Secessió vienesa, un moviment artístic que es va formar el 1897 per un grup de pintors, dissenyadors gràfics, escultors i arquitectes austríacs, entre ells Josef Hoffman, Josef Maria Olbrich, Koloman Moser, Otto Wagner i Gustav Klimt, artistes que van trencar amb els estils artístics tradicionals.

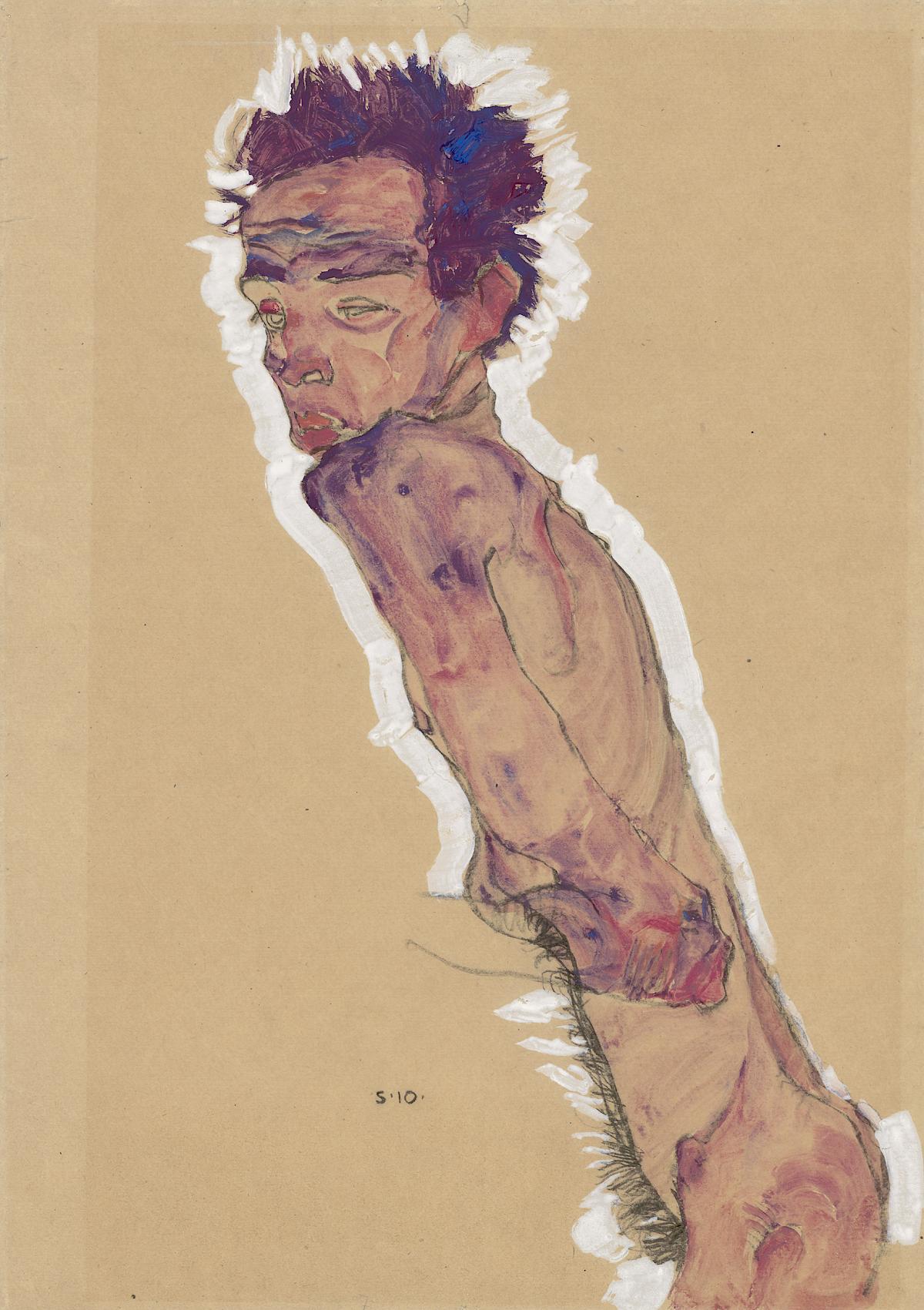

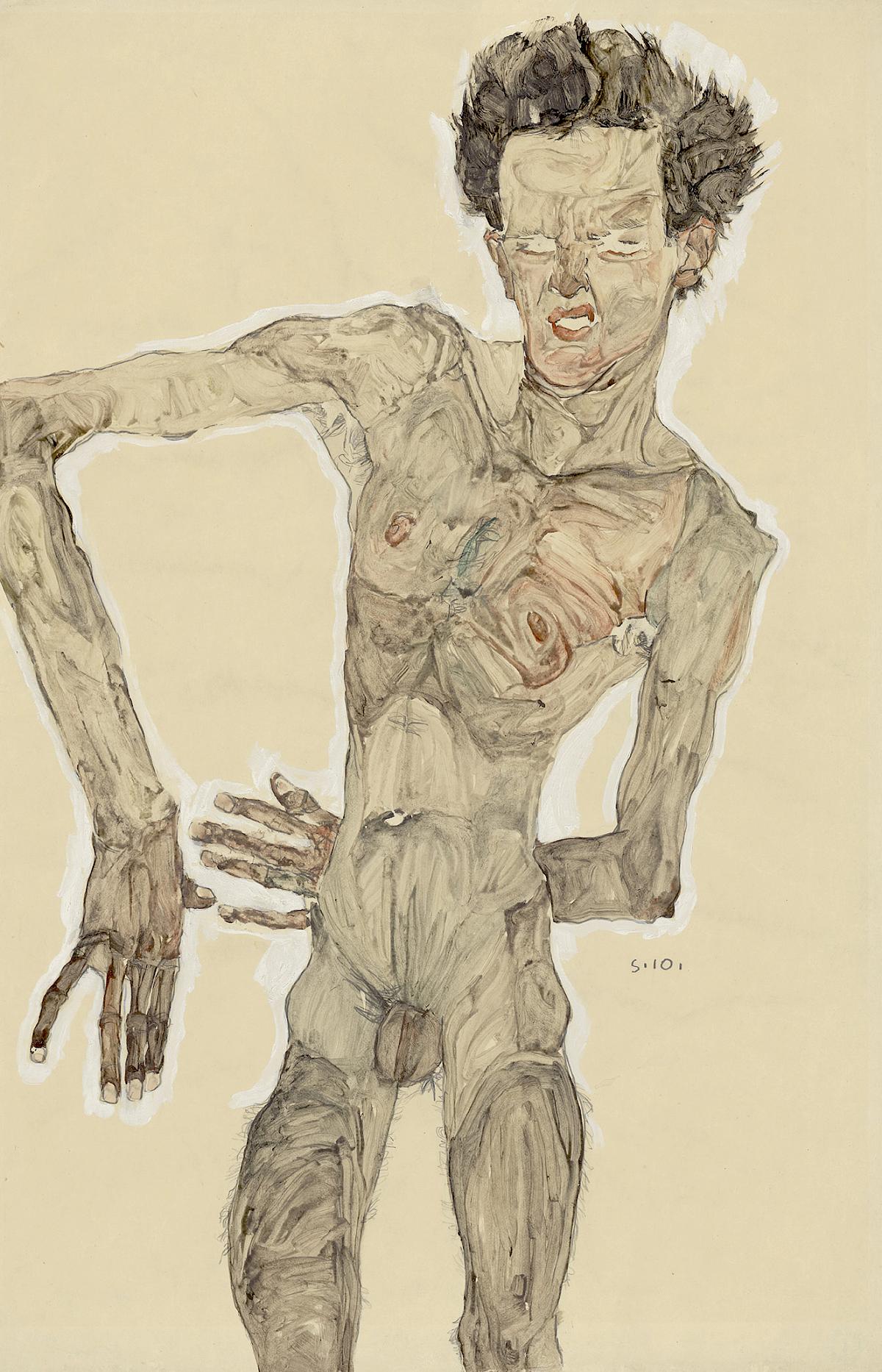

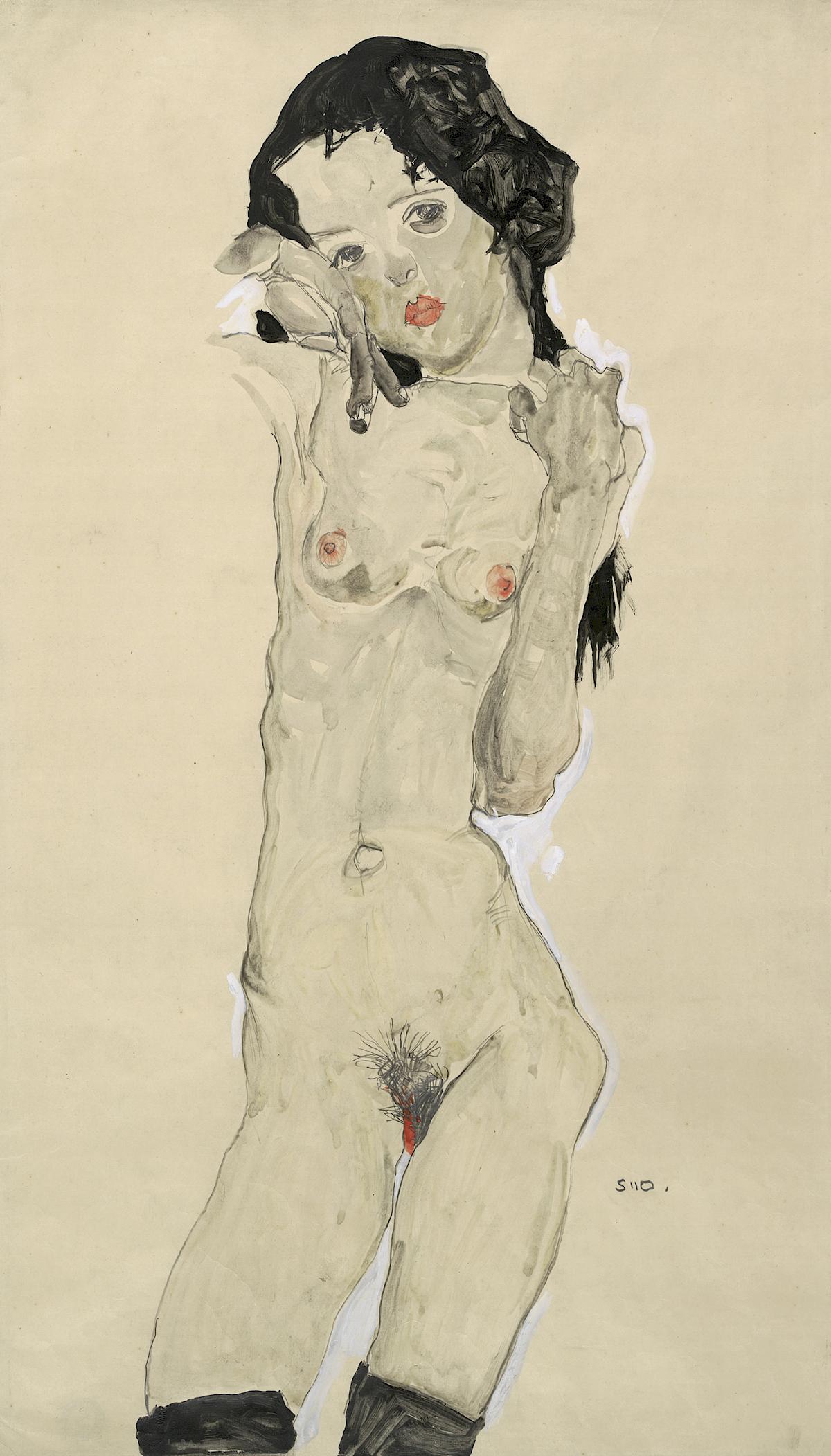

Egon Schiele. Nude Self Portrait (1910). The Albertina Museum, Viena. Foto: AM

Schiele, però, té un estil molt personal, una forma de dibuixar i pintar diferent dels altres artistes de la Secessió, les seves obres reflecteixen els seus estats d’ànim ombrívols, la seva personalitat complexa i segurament neurótica i les seves relacions amoroses / eròtiques. Quan veiem els seus autoretrats, és inevitable pensar que van ser pintats per una persona amb trastorns mentals, però, cal remarcar que en el canvi de segle va haver-hi molt interès en el vincle entre l’art i la malaltia mental. Artistes que dibuixaven rostres i gestos de bojos i psiquiatres que estudiaven els dibuixos i les pintures dels malalts mentals per intentar comprendre les seves conductes. Així mateix, pintors i escultors de l’Expressionisme van intentar plasmar rostres estranys, rars, allò grotesc en l’ésser humà que, de vegades, procedeix de la malaltia mental. No era nou. Al segle XVIII, l’escultor germano-austríac Franz Xavier Messerschmidt va realitzar una sèrie de bustos amb rostres contorsionats, expressions facials extremes, pròximes a allò patològic. Ell mateix era considerat un llunàtic. És possible que Schiele hagués vist aquests busts a Viena i s’hi hagués inspirat. Goya va plasmar en pintures i gravats personatges els quals podem analizar com a trastornats; pintors de segle XIX van utilitzar els rostres de delinqüents i malalts mentals com un experiment per tal de concretar pictóricament estats d’ànim. Leonardo da Vinci també ho va fer. I els artistes surrealistes no estaven pas allunyats d’aquests procediments.

A l’obra The Hermits, les dues figures de mida natural que impressionen moltíssim quan la tens al davant, participen d’aquest art on es pot bussejar per patologies diverses. Una de les figures de The Hermits és el mateix Schiele, i l’altra, que sembla muribunda, no hi ha acord entre els especialistes: podria ser Gustav Klimt, el seu pare o Sant Francesc d’Assís. Schiele va escriure una carta al seu col·leccionista i mecenes Carl Reininghaus en la qual li diu que aquesta pintura mostra un món de dol en què els dos cossos es troben a si mateixos:

Els cossos d’aquells que estan cansats de la vida, suïcides i, no obstant això, cossos plens de sentiment. Penseu en les dues figures com un núvol de pols similar a la terra que desitja amuntegar i colapsa per falta d’energia.

Egon Schiele. Two Women (1915). Albertina Museum, Viena. Foto: AM

El crític alemany Max Nordau va encunyar el terme Entartung (degeneració), un terme que els nazis van utilitzar més tard amb un efecte tan nefast que va fer possible condemnar les obres d’art alienes a unes normes tradicionals tot titllant-les de “malaltes”, degenerades. Era una acusació contra la qual també es va haver de defensar a Schiele. Va pintar persones degenerades? Quan es va pintar a si mateix, va pintar a un home degenerat? Parlem de malaltia mental o de dolor extrem en el seu cas? O les seves figures, homes i dones són, de fet, ninots indefensos? A vegades ho semblen.

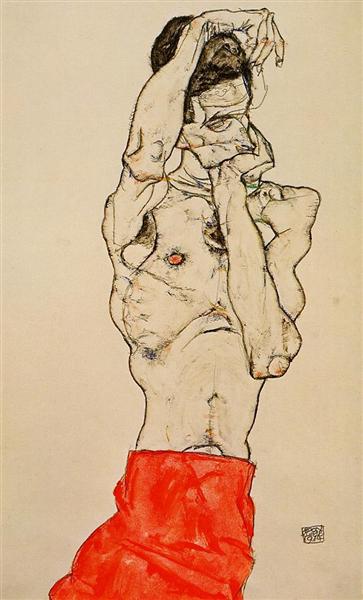

Egon Schiele. Standing Male Nude with Red Loincloth (1914). The Albertina Museum, Viena. Foto: Wikiart

El dilema amb Egon Schiele consisteix a esbrinar si els seus pertorbadors autoretrats poden expressar l’essència mateixa de tota una època o són simplement un tret d’una personalitat que podríem considerar narcisista. L’enorme quantitat d’autoretrats que ha deixat, uns cent, mostren que certament va dedicar un escrutini maníac a la seva pròpia persona i li agradava molt plasmar la seva pròpia aparença i poses. De totes maneres, no és el primer artista que es retrata a si mateix. Dürer, Rembrandt, Ferdinand Hodler i Van Gogh van usar el mirall per registrar la seva pròpia aparença moltes vegades i així establir un relat autobiogràfic.

Podem dir que els autoretrats de Schiele són un reportatge autobiogràfic i, evidentment, molt narcisistes, però segons l’historiador de l’art de la Universitat de Stuttgart, Reinhard Steiner, van més enllà: “Les poses que realitza en ells són extraordinàries, els seus gestos altament efectius i els retrats neguen i desmantellen la unitat del jo. Es crea una tensió entre el jo real i el jo vist en forma alienada en la imatge i aquesta tensió no testifica la certesa confirmada de la identitat individual sinó més aviat la seva fi. Alguns dels autoretrats poden recordar El retrat de Dorian Gray (1890) la novel.la d’Oscar Wilde, en què el jo pintat envelleix mentre que la bellesa del jo real roman inalterada. La imatge en el seu mirall li va servir a Schiele no com una forma de fixar la seva identitat, sinó per promoure la recerca de l’altre jo que retratava a les seves imatges”.

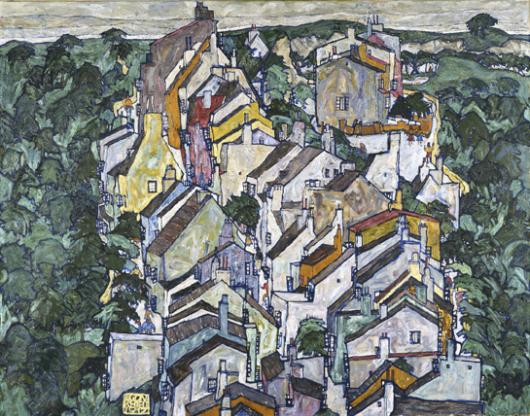

Biografia

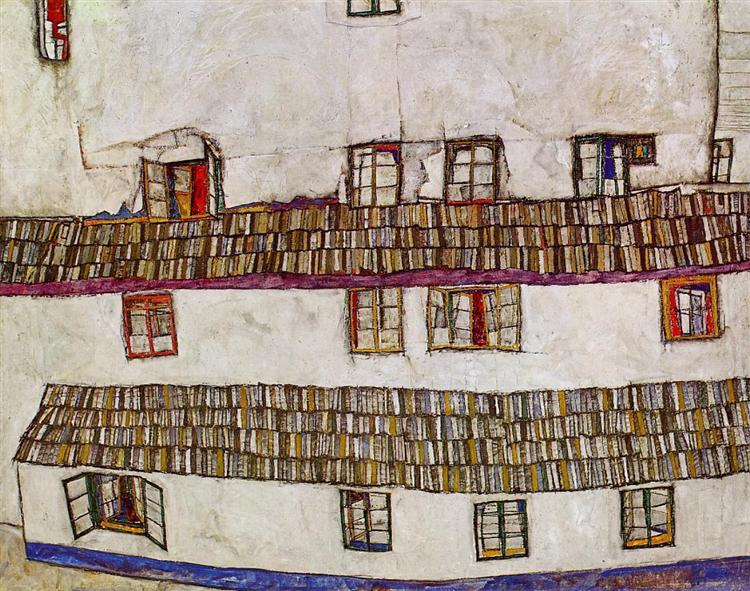

Egon Schiele va néixer el 2 de juny de 1890 a Tulln, un petit poble prop de Viena, el tercer dels quatre fills d’Adolf Eugen Schiele, un cap d’estació dels Ferrocarrils Imperials Austríac-Hongaresos, originari del nord d’Alemanya, i de la seva esposa Marie, originària de Krumau, Bohèmia. Va ser del seu pare que Egon va heretar la seva afició de tota la vida pels trens. El seu avi també havia estat enginyer ferroviari. Els seus primers dibuixos de la infància van ser de trens i els seus paisatges urbans amb la seva cadena ininterrompuda d’unitats visuals en horitzontal, a vegades donen la sensació que plasmen la vista des de la finestra d’un tren, o be pinta unes fileres de cases semblen vagons de trens. Viatjava en tren amb freqüència i d’adult va seguir jugant amb trens de joguina.

Egon Schiele. Facade with windows (1914). Belvedere Museum, Viena. Foto: Wikiart

El 1902, el seu pare va ser jubilat forçosament per una malaltia mental i va morir dos anys més tard quan Egon tenia 14 anys. Estimava molt al seu pare, hi estava molt unit i la seva mort li va suposar una commoció terrible. I va començar a dibuixar i pintar sense parar, inclosos els seus primers autoretrats, deia que el seu pare li parlava en somnis. Reinhard Steiner assenyala que els seus vistosos primers autoretrats (de 1905 a 1907) són l’intent de Schiele d’utilitzar versions exhibicionistes de si mateix per compensar l’absència dels afectuosos elogis que li dedicava el seu pare: “Després de la mort del seu pare, l’autoretrat va ser presumiblement una forma ideal perquè Schiele compensés la pèrdua d’algú que fou tan important per a ell i l’aprovació del qual ara trobava a faltar”. Un mètode, encara que egòlatra, que reemplaçava la imatge perduda i idealitzada del pare.

Egon Schiele. Self-Portrait with Striped Shirt (1910). Leopold Museum, Viena. Foto: artsy

A part de les dificultats econòmiques que va provocar la seva pèrdua a la família, va sentir encara més la manca del pare perquè no tenia una bona relació afectiva amb la seva mare, la qual cosa va empitjorar quan es va convertir en “l’home de la casa” encara que sota la supervisió del seu tutor, el seu oncle i padrí, Leopold Czihaczek. Egon va créixer al costat de dues germanes: Melanie i Gertrude (Gerti). Gerti va ser model freqüent de Schiele i més tard es va casar amb el seu amic íntim, el pintor Anton Peschka. La mort no era aliena a la família Schiele, dos infants van néixer morts i un altre va viure només fins als deu anys. Schiele solia dir que la mort el va modelar com a artista, es va convertir en un tema principal.

Egon Schiele. Gerti Schiele (1909). MoMa, Nova York. Foto: Wikicommons

Schiele era un nen feble i reservat que preferia la seva pròpia companyia a la dels altres. No va ser un alumne brillant a l’escola i fins i tot va haver de repetir un any, deia que els seus mestres toscs eren els seus enemics. Per l’única cosa que tenia entusiasme era pel dibuix. El seu mestre de l’escola Klosterneuburg, Ludwig Karl Strauch, el pintor Max Kharer i Wolfgang Pauker, mestre del cor agustí, van donar suport les seves primeres iniciatives artístiques. A la primerenca edat de 16 anys va ser acceptat a l’Acadèmia de Viena, animat pels mestres abans esmentats i contra el desig del seu tutor, Leopold Czihaczek. Es va matricular a la classe de Christian Griepenker, però el seu pas per l’acadèmia no va ser notable, tot i que posseïa un do natural i la millor destresa per al dibuix. L’Acadèmia requeria d’ell una disciplina: l’estudi de l’estatuària antiga, dels models vius i de les vestidures i exercicis de composició. Schiele tenia aversió als exercicis acadèmics, encara que cal dir que el van ajudar a perfeccionar el do de dibuixant que ja posseïa.

La relació amb la seva mare va ser molt complicada. Ella va recolzar el seu desig d’assistir a l’Acadèmia de Viena, no obstant això, havia de garantir les despeses del seu fill estudiant i els de la família i els diners no sobraven. Sembla que el problema era ell. Steiner el descriu durament: “Difícilment se’l podria anomenar un fill agraït. Obsessionat amb la idea de la seva vocació artística, va donar per fet que la seva mare faria sacrificis per ell, especialment quan la mort del seu pare el va deixar com a cap de família. Sembla que es va acarnissar amb la seva mare, la sentia com una estranya”. A causa de la precària situació econòmica, la mare esperava un major suport del seu fill i, des del seu punt de vista, no estava entusiasmada amb la perspectiva d’un fill artista, especialment perquè aquestes perspectives implicaven un estil de vida que li deuria semblar irresponsable. “Amb tot, Schiele li va exigir una voluntat gairebé incondicional de fer sacrificis i subordinació a la seva pròpia voluntat, i això va fer que el conflicte fos inevitable”.

Egon Schiele. Blind Mother (1914). Leopold Museum, Viena. Foto: Wikicommons

Qualsevol que sigui la nostra visió moral d’aquest conflicte, Schiele el va confrontar en els seus quadres. La mare apareix en una sèrie de variacions del tema de la mare i el nen que desprenen molta amargor, reflecteixen una maternitat infeliç, gairebé insuportable. Els títols per si sols ja són esgarrifosos: mare morta, mare cega, etc. Hi ha testimoni escrit d’aquesta relació. La seva mare el maleeix en una carta. I la resposta a la maledicció de la mare va ser:

Estimada mare! (…) Em fas una injustícia…vull gaudir del plaer que tinc al món, per això sóc creatiu, i ai! qui m’ho robi. El vaig treure del no-res, i ningú no em va ajudar, només m’haig d’agrair a mi mateix per la meva existència.

Per a Stenier aquesta resposta només pot llegir-se com “un exemple clàssic de narcisisme ferit i només ell sembla estar pretenent entendre i intentar un compromís”.

Egon Schiele. Dead Mother (1910). Leopold Museum, Viena. Foto: Wikicommons

Dead Mother és una de les obres més esfereidores de la seva carrera. La va pintar amb només 20 anys. Li va escriure al seu amic, l’historiador de l’art Arthur Roessler, qui va ser el primer propietari de la pintura:

Només ara m’adono que Dead Mother és una de les meves millors obres.

Roessler va rebre la pintura com a regal de l’artista i la va penjar en el seu estudi. Cada part de l’escena traspua la tragèdia inherent del tema, un nen que es reconeix que segueix viu però atrapat en una mare sense vida, la pintura mostra desesperació, venjança o malentesos i… misogínia. Al Leopold Museum es descriu la pintura de la següent manera: “Les faccions de la mare estan demacrades, els seus ulls trencats i el seu cap gira de forma poc natural cap a un costat mentre abraça tendrament al seu fill. El llenguatge del color ho diu tot. La pell de la mare està representada en colors freds i terrosos: la vida s’ha acabat, el seu cos és una closca morta per al nen que va crèixer dins d’ella. El nen sembla desesperadament perdut; encara que la seva pell de color taronja i carmesí signifiqui vitalitat i vida, la mort de la mare segellarà el seu destí, a més del seu”. En el context de l’època, aquesta pintura i les de la sèrie sobre la mare, se situen en la tradició de la pintura simbolista que vinculava estretament la maternitat i la por a la mort. Era un fet, en aquesta època, moltes dones morien en el part i la mortalitat infantil era molt alta. I com ja he esmentat la mort va visitar massa vegades a la família Schiele.

Egon Schiele. Standing Girl in Checked Cloth (1910). The Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Foto: MIA

Quan Egon Schile va iniciar la seva curta carrera, Viena vivia una efervescència artística amb la Secessió, amb Gustav Klimt (1862-1918), com un dels representants més destacats, l’estil del qual el va influir notablement. Va quedar impressionat pel seu estil lineal de dimensions planes i pels artistes de la Secessió. Schiele va declarar la seva afinitat amb el moviment. Mentre estava a l’Acadèmia gairebé un adolescent, Klimt es va convertir en el seu estel, i el va reverenciar fins a la seva mort. Aquesta elecció en si mateixa va ser un acte de rebel·lió contra la instrucció de l’Acadèmia, molt tradicional. Schiele va adoptar els principis de Klimt, sobretot l’èmfasi en la superfície plana, un fi dibuix i uns valors decoratius dels quals ja se’n distanciava. Tenen una gran influència de Klimt el retrat ja esmentat de la seva germana Gerti i les obres Standing Girl in Checked Cloth i Water spirits, però la seva pròpia personalitat i el seu inconfusible estil ja hi és. Amb tan sols 18 anys, el 1908, va exposar la seva obra per primera vegada a Klosterneuburg. Un any després va deixar l’Acadèmia, on no li va anar bé, ja que com s’ha dit no suportava els seus tradicionals mètodes d’ensenyament. LLavors, va fundar l’efímer Neukunts-gruppe (Grup d’Art Nou) amb els seus amics i antics alumnes de Griepenkerl, Anton Faistauer, Karl Massmann, Anton Peschka, Franz Wiegle i altres. Però va deixar el Grup després d’una primera exhibició que no va tenir èxit a la Galeria Pisko de Viena i va decidir “anar sol”. Volia una exposició individual.

Egon Schiele. Nude Woman Lying on her Stomach (1917). The Albertina Museum, Viena. Foto: Wikiart

A partir de 1909, Schiele va deixar cada vegada més enrere l’elegant claredat lineal de Klimt i va desenvolupar un estil de dibuix que fins i tot el mateix Klimt va reconèixer com l’estil d’un mestre. La primera reunió dels dos artistes probablement va tenir lloc el 1910. Schiele li va preguntar a Klimt si podien intercanviar obres, dient-li ingènuament que amb gust li donaria diversos dels seus propis dibuixos per un de seu. Klimt va respondre: -Per què vols intercanviar-los amb els meus? De totes maneres, dibuixes millor que jo … Klimt va acceptar de bon grat l’intercanvi i també li va comprar alguns dibuixos més. El 1910, després de la seva primera exposició individual, va escriure en una carta al Dr. Josef Czermak:

Vaig passar per Klimt fins al març. Avui, crec, sóc el seu oposat …

I evoluciona cap al seu propi i determinant estil. La seva ambició era tanta i estava tan segur de si mateix -o ho volia demostrar- que va escriure:

Els meus cuadres s’han de col·locar en edificis com temples.

Egon Schiele. Fighter (1913). Colecció privada. Foto: Wikimedia

I es pinta i dibuixa a si mateix una i una altra vegada. Distorsionat, molt prim, gairebé esquelètic, les expressions facials ombrívoles i estranyes, de mirades ferotges, de vegades, sembla un home paranoic i se suposa que es contempla al mirall, però, el personatge representat a la pintura és realment ell? Vistos aquests autoretrats en conjunt se’ns apareix un jo múltiple on encara que sembli una paradoxa formen un concepte visual unitari. Com diu Steiner, Schiele es veia a si mateix com una mena de sacerdot de l’art, més visionari que acadèmic, veia i revelava coses que romanen ocultes a la gent normal. Encara que ho són i a ell el reconeixem, no és fàcil veure els quadres com autoretrats ja que en el seu estil no parlem pas en termes de realisme mimètic. De vegades, esdevenen un enigma. Val a dir que no és gens complaent amb ell mateix, no es pinta pas atractiu ni agradable, al contrari, les seves mirades poden ser molt malèvoles, la perversitat emana de la seva pell, no pretén pas agradar a l’espectador. De totes maneres, potser, per a ell tot plegat és una altra cosa. Va sentenciar:

Crec que els pintors més grans van pintar la figura humana. Jo pinto la llum que emana dels cossos

Krumau

Egon Schiele.View of Krumau (1916). Wolfgang-Gurlitt Museum, Linz. Foto: KRI

Es va traslladar a Krumau, al sud de Bohèmia, d’on era la seva mare. Va escriure a Anton Peschka que se sentia desgraciat a Viena:

Tots conspiren contra mi, els antics col·legues em miren amb ulls malèvols. A Viena hi ha ombres.

Va llogar un estudi juntament amb Erwin Osen, un artista membre del New Art Group, un excèntric pintor d’escenografies que havia rebut l’encàrrec de realitzar dibuixos de pacients mentals del manicomi de Steinhof per a il.lustrar una conferència sobre expressions patològiques en retrats. A Krumau, Schiele es va girar cap a la natura, volia sentir-la al bosc de Bohèmia. Va escriure:

Vull contemplar amb sorpresa les tanques de jardí rovellades. Vull experimentar-ho tot, escoltar les plantacions de bedolls joves i les fulles tremoloses, veure la llum i el sol, gaudir de les valls verd blau a la nit, sentir la brillantor dels peixos de colors, veure núvols blancs com s’acumulen al cel, parlar amb les flors, amb les velles esglésies venerables per saber el que diuen les petites catedrals, per córrer sense aturar-me per les corbes dels prats a través de vastes planes, besar la terra i olorar les flors suaus i càlides dels aiguamolls. I després donaré forma a les coses de manera tan bonica: camps de color …

Va escriure sobre la naturalesa però de fet a Krumau va produir nombrosos nus. Poc després d’instal·lar-se Krumau va arribar la Valery (Wally) Neuzil. En realitat, se sap molt poc d’ella, era filla il·legítima d’un jornaler i una mestra i va néixer en un poble al sud de Bohèmia. La va conèixer el 1911 quan ell tenia 21 anys i ella 17. Sembla que havia estat una model de Klimt, probablement una de les seves amants, seria el mateix Klimt qui li va presentar la Wally a l’Egon i li “cediria” la noia. Amb ella passaria els propers quatre anys. Va ser la seva model preferida, apareix en la majoria dels seus dibuixos eròtics i en diverses de les seves més pintures importants.

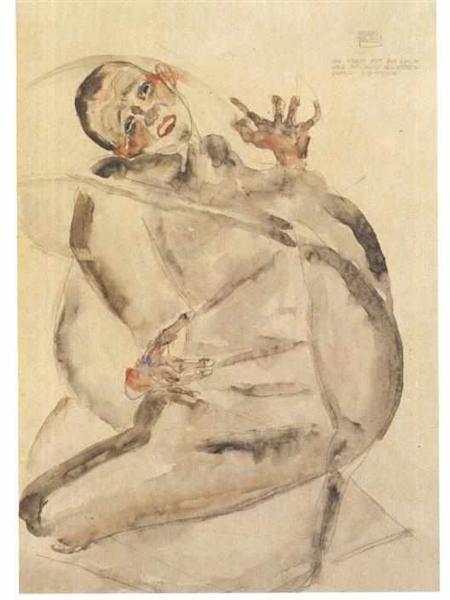

Cos nu

Per a Schiele el cos nu es va convertir en el tema principal de la representació del jo des del 1910 en endavant. Ja he esmentat simbòlicament la relació del subjecte amb la mort del seu pare, però, va molt més enllà. Per a ell, el nu és la forma més radical d’autoexpressió perquè creu que amb el cos exposat tal qual, sense els vels de la roba o amb poca, el jo es captura completament. Per aquest motiu el mostra gairebé sempre en un espai buit, sense accessoris. Schiele neutralitza el “fons” mitjançant l’ús d’una unidimensionalitat monocromàtica que fa que els cossos semblin insegurs i confereix als seus moviments una qualitat espasmòdica o nerviosa. Els contorns irregulars i angulars de les figures, que contrasten de manera molt marcada amb aquests fons neutres, contribueixen a la desfamiliarització de la imatge natural i possibiliten una major expressivitat física amb unes pinzellades àmplies i bruscament juxtaposades que transmeten una energia, a vegades desbordada, a vegades pertorbadorament continguda.

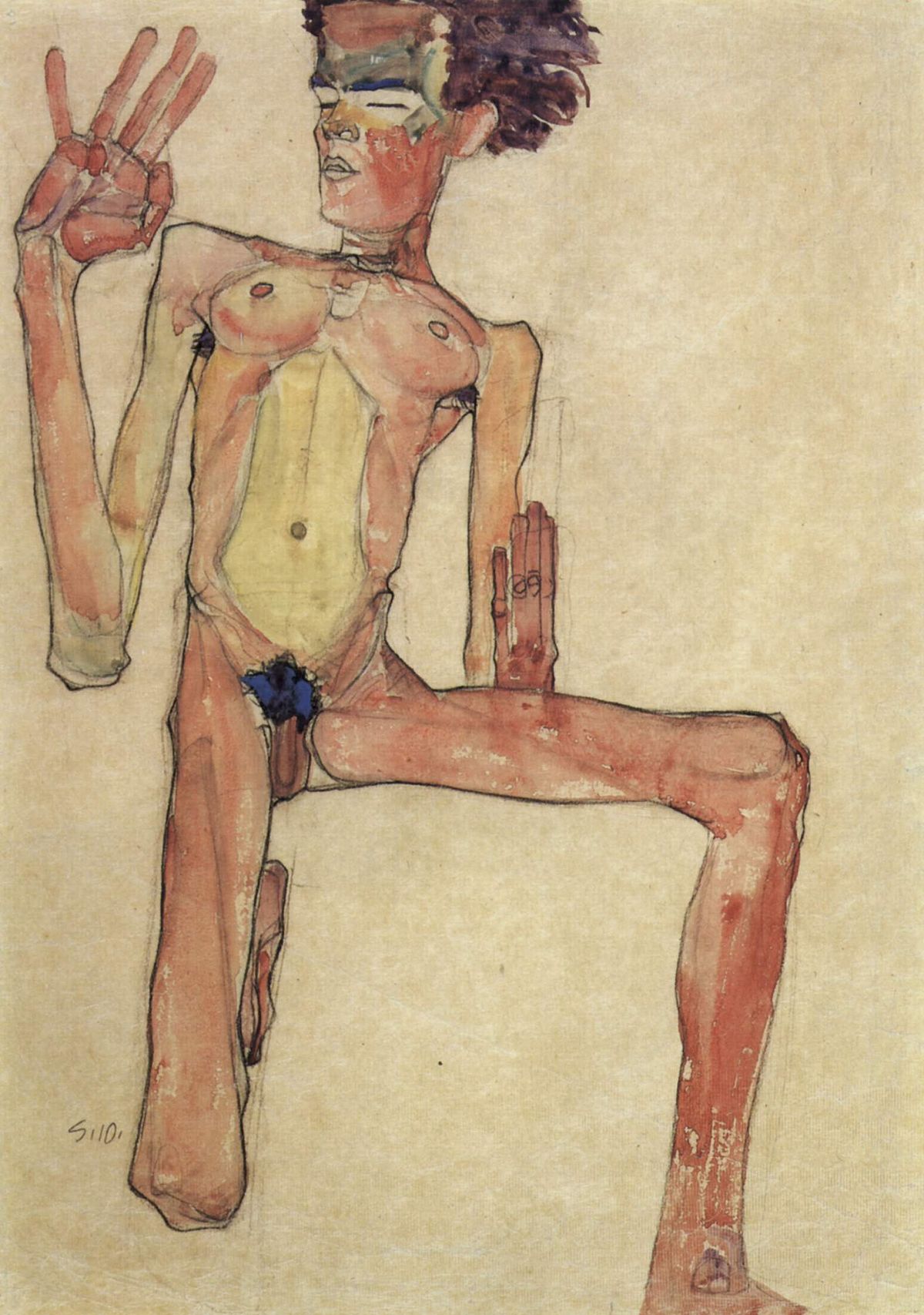

Egon Schiele. Seated Nude Male (1910). Col.lecció privada. Foto: wikicommons

Particularment, quan mutila el cos fins convertir-lo en un simple tors que poc té a veure amb una aparença normal, com si fossin ninots trencats. Va escriure en una carta al Dr. Oskar Reichel, un dels seus col·leccionistes, el 1911:

Quan em vegi complet, hauré de veurem a mi mateix i saber el que vull, no només el que està succeint dins de mi, sinó també fins a quin punt tinc la capacitat de mirar, quins mitjans són els meus, de quines substàncies enigmàtiques estic fet i de quanta d’aquesta major part percebo i he percebut fins ara en mi mateix. Em veig esvaïnt-me i exhalant cada vegada més, les oscil·lacions de la meva llum astral són cada vegada més ràpides, directes, més simples i com una gran visió de món. Així que constantment assoleixo més, produeixo més i infinitament més coses brillants des de dins de mi, en la mesura que l’amor, que ho és tot, em dota d’aquesta manera i em porta a allò que instintivament m’atrau, al que vull arrossegar cap a mi, per fer alguna cosa nova un altre cop que he vist malgrat jo mateix.

És obvi que els seus autoretrats nus presenten un alt grau de narcisisme i exhibicionisme. Però a part d’això, l’artista mateix, nu, s’exhibeix al capdavall com una criatura sexual. Pot ser que Schiele estigués disposat a exorcitzar dimonis sexuals i vivia en la seva imaginació “impulsos que no sempre podien satisfer-se en la realitat. En altres paraules, retratar els impulsos i les passions d’un mateix és afrontar-les”, puntualitza Steiner. De tota manera, els amics de Schiele no el van pas descriure com un erotomaníac desenfrenat. Malgrat l’aspecte freqüentment desagradable i torturat de la seva nuesa, Steiner creu que seria un error exagerar-ne el component eròtic. El que sembla més important (i s’expressa en les seves cartes i poemes) és el fet que Schiele va posar un gran èmfasi en la comprensió i l’exploració del jo: “Aquesta exploració no va ser una cosa mística, anti-física per a ell; més aviat, era una forma de localitzar energies a través del cos com a substància espiritual”.

Egon Schiele. Self-Portrait with Arm Twisted above Head (1910). Col.lecció privada. Foto: Neue Gallery

D’altra banda, Schiele pertany a la Secessió Vienesa, però els seus nus són ben expressionistes. Des del 1909 va començar a desenvolupar la seva pròpia tendència expressionista i va abandonar l’estil decoratiu associat amb la Secessió i amb el Jugendstil. Paul Hatvani, en el seu “Essay on Expressionism” (1917) ho defineix clarament: “L’obra d’art expressionista no només està connectada sinó que és idèntica a la consciència de l’artista. L’artista crea el seu món a la seva pròpia imatge”. L’observació de Hatvani assenyala el camí cap a una reinterpretació del mite de Narcís, que es pot aplicar no només als autoretrats sinó a tota l’obra de Schiele: “El Narcís modern no crea una imatge artística que reprodueixi la forma real de les coses, més aviat, inverteix l’escrutini en perspectiva del món i en aquesta inversió el jo o subjecte mateix es converteix en l’horitzó, el jo que inunda el món”.

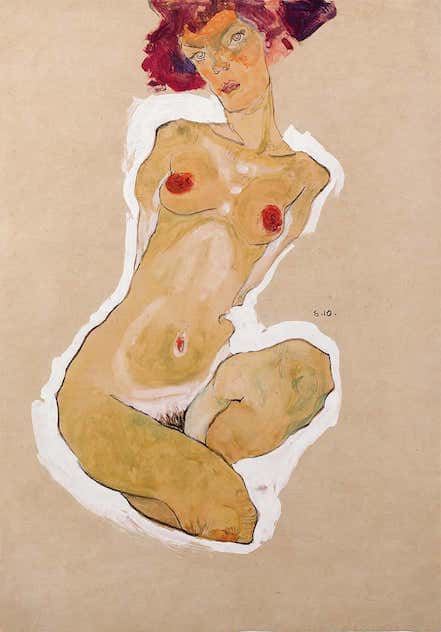

Els dibuixos eròtics de Schiele són inquietants pel fet que l’artista va subvertir les convencions establertes. Les dones, en lloc de ser receptacles passius del desig masculí, s’ofereixen, els seus cossos són francament excitants. A l’ometre qualsevol detall circumdant dels seus dibuixos i donar amb freqüència a les figures reclinades una lectura vertical, va crear una profunda sensació de dislocació espacial. Fins i tot per als estàndards actuals, aquests dibuixos atorguen a les dones un alt contingut sexual, encara que vagin mig vestides. Però per sobre de tota controvèrsia o exàmen sobre la seva personalitat, Egon Schiele va ser un dibuixant genial. La línia de Schiele sembla fràgil i constreta, molt personal. Sovint és fragmentària, gairebé mai recta o arrodonida. S’interromp i es torna més o menys contundent depenent de l’èmfasi que posarà en un detall particular. I, no obstant això, la línia sempre és tan segura i controlada! Ho abraça i ho contè tot.

Egon Schiele. Heinrich and Otto Benesch (1913). Neue Gallery, Linz. Foto: Wikicommons

L’historiador de l’art austríac Heinrich Benesch el va veure dibuixar i ho va descriure de la següent manera: “La bellesa de la forma i el color que ens va donar Schiele no existia abans. El seu art com a dibuixant va ser fenomenal. La seguretat de la seva mà va ser gairebé infal·lible. Quan dibuixava, generalment s’asseia en un tamboret baix, el tauler de dibuix i el full sobre els seus genolls, la seva mà dreta (amb la qual dibuixava) descansava sobre el tauler. Però també el vaig veure dibuixar de manera diferent, parat davant de la model, el seu peu dret en un tamboret baix. Després donava suport a la taula sobre seu genoll dret i la sostenia en la part superior amb la mà esquerra, i la seva mà dibuixava sense suport, col·locava el seu llapis sobre el full i traçava les seves línies des de l’espatlla, per dir-ho. I tot estava perfectament. Si s’equivocava en alguna cosa, la qual cosa era molt rara, tirava el full; mai va fer ús d’una goma d’esborrar. La majoria dels seus dibuixos estaven fets amb contorns i només es tornaven més tridimensionals quan estaven acolorits. La coloració sempre la va fer ‘sense’ el model, de memòria”.

Neulengbach

El 1911 es va veure obligat a deixar Krumau. La gent del poble es va escandalitzar amb estil de vida de Schiele i del fet que els nens posessin per a l’artista nus en el seu estudi; també per la presència de Wally, que posava nua per a ell. En el canvi de segle, del XIX al XX, les models d’artistes, de vegades, es veien en una posició propera a les prostitutes, era mal vistes, però, podia passar que l’artista s’enamorés d’elles, amb la qual cosa la seva posició es feia més respectable, però no va anar així per a la pobre Wally.

Egon Schiele. Two Young Girls (1911). The Albertina Museum, Viena. Foto: AM

L’Egon i la Wally van trobar un nou lloc per viure a Neulengbach, a l’oest de Viena. Un any després estava detingut i traslladat a la presó de St. Pölten, els seus dibuixos eròtics confiscats i acusat de “seduir” i “violar” a una menor d’edat. Pel que fa a l’acusació de violar una menor sembla que no va tenir lloc. Jane Kallir, autora del catàleg raonat de Schile, explica: “L’incident va ser precipitat per una adolescent fugitiva, que va demanar a l’Egon i la Wally que la portessin amb la seva àvia a Viena. Un cop a la ciutat, la nena es va refredar i els tres van tornar a Neulengbach un dia després. Mentrestant, el pare de l’adolescent havia presentat càrrecs de segrest i assetjament sexual infantil, el que va portar a la policia a realitzar una investigació exhaustiva de l’artista”. En el curs de la investigació, en el registre de casa seva la policia va trobar dibuixos eròtics en el seu estudi i va formular el càrrec de delicte d’”immoralitat pública” perquè els menors que passaven l’estona en el seu estudi després de l’escola els havien vist.

El seu amic Heinrich Benesch el va defensar dient que Schiele pintava models infantils en el seu estudi i sovint deixava que entressin a la seva habitació els nens i nenes companys d’escola dels models que posaven per a ell. Schiele havia penjat a la paret un dibuix d’una nena vestida només de cintura cap amunt i els nens que ja no eren del tot innocents van murmurar i van parlar, i així va ser com van sorgir els càrrecs; el dibuix en questió va ser posteriorment destruït per ordre del tribunal. En el judici a St. Pölten es va retirar el càrrec d’abús sexual i només se li va imposar una pena de presó de tres dies per exhibir uns dibuixos immorals on eren visibles per als nens, una sentència que va tenir en compte el fet que ja havia passat tres setmanes sota custòdia en el moment del judici. Sembla que en la seva defensa Schiele va afirmar:

Sóc un artista. La meva responsabilitat és defensar la llibertat de l’art.

L’any 2018, enmig del mar de denúncies per assetjament sexual vinculades al moviment #MeToo el New York Times va incloure a Egon Schiele en la seva llista d’artistes abusadors. Val a dir que la Wally el va recolzar durant tot l’assumpte Neulengbach, el veia innocent, va ser la que li va portar a la presó subministraments de pintura i li va trobar un advocat.

Egon Schiele. Self Portrait as a prisoner (1912). The Albertina Museum, Viena. Foto: Wikiart

A la presó va fer tretze aquarel·les que registren la seva experiència. Apareix com una víctima devastada, amb expressions temoroses i turmentades a causa de l’aïllament i l’empresonament. Va escriure en els dibuixos frases com:

Em sento més purificat que castigat.

Impedir a un artista és un crim. Fer-ho és assassinar una vida que floreix.

Des del punt de vista compositiu, Steiner considera que els dibuixos de Neulengbach es poden veure com a exemples extrems d’experimentació amb la seva pròpia persona, el seu tema preferit. Les poses són artificials i en la majoria d’elles es pinta amb gestos i expressions facials molt exagerades.

Egon Schiele. The Embrace (1917). The Belvedere Museum, Viena. Foto: BM

A part de la questió moral, Schiele va pintar temes eròtics tota la seva vida, homes i dones, junts o separats. En aquest moment, la moral de la societat oficial, que era era beata i intolerant, es va ofendre amb els seus nus. Són tan toscs, tan “reals”, fins i tot pornogràfics, que no donen a l’espectador l’oportunitat de mantenir la distància. Els seus nus agressius, masculins o femenins, els pintava sense el full de figuera del mite que tapa, esdevenen un escrutini obsessiu que no evita el caràcter i la mirada sexual. I encara avui cal reconèixer que poden ofendre a molta gent puritana que els veuen com una immoralitat i una obscenitat. Com assenyala Steiner, “els seus nus moralment parlant en posicions dubtoses el van portar a la presó”. Aquest episodi va establir una imatge romàntica de l’artista incomprès, producte de la moral de l’època. Avui, com a artista conegut, el que va passar a Neulengbach, seria un tema explotat per la premsa fins a la sacietat i probablement investigada i condemnada la seva relació amb els menors que va pintar, com apunta el New York Times.

Egon Schiele. Seated Woman with Left Leg Drawn Up (1917). Národní Gallery, Prague

Les relacions de Schiele amb les dones són difícils de jutjar, no només perquè no en sobreviuen testimonis vius ni elles n’han deixat res escrit, sinó també perquè els estàndards actuals són molt diferents dels que prevalien a l’Àustria de principis del segle XX. Per a Jane Kallir, Schiele, per descomptat, no era una feminista, ni ho era Klimt, ni la majoria dels artistes d’aquesta època, aquest concepte ni existia tal com l’entenem ara: “Les opinions actuals sobre el gènere han trigat dècades a gestar-se, i ell va ser en gran mesura un producte del seu temps i lloc. No obstant això, a diferència de molts homes, llavors i després, Schiele va abraçar la barreja de por i atracció i va pintar les respostes masculines cap a “l’altre” femení. Com a resultat, va crear imatges de dones que, reflectint la seva pròpia ambivalència, dominen audaçment la seva sexualitat. És aquesta sexualitat realment una espècie de superpoder, o l’atractiu femení implica inevitablement la capitulació davant el patriarcat? La rellevància perdurable del gran art rau en tals preguntes, en lectures ambigües més que en formulacions simplistes. Qualificar a Schiele de delinqüent sexual no només un error; ignora el context històric essencial i exclou el diàleg necessari.”

Una altra de les seves sentències:

Les obres d’art eròtiques també són sagrades.

Però la pregunta és si va ser només un voyeur com Klimt. Probablement no, va ser molt més que això. Benesch creu que el que primer crida l’atenció de les seves obres eròtiques (així com dels seus nus) és que abandona l’ús normal de la perspectiva, el que proporcionaria una justificació per a les posicions en què apareixen les seves figures. Antiacadèmic des del principi al final, dissenya angles i punts de vista des dels quals les figures apareixen recargolades, contorsionades o deformades, rarament vistes de manera frontal o hieràtiques, estableix poses desconegudes i alienants, moviments estranys. Si el comparem amb el seu adorat Klimt, els nus femenins de Klimt són com “somnis de desig”, però estan protegits, en els de Schiele les poses forçades despullen radicalment a la model i la deixen exposada i indefensa. Aquests cossos gairebé mai estan relaxats. Generalment es retorcen d’una manera gairebé acrobàtica, s’exhibeixen, s’ofereixen: “Schiele lliga metafòricament el seu model a una taula d’operacions en el seu laboratori òptic, i examina l’espècimen amb una mirada clínica, disseccionant la criatura a la seva mercè amb el seu llapis. És així que la majoria dels seus nus no semblen íntims ni absorts en les seves pròpies paraules, sinó aïllats i tensos, sovint ens miren a la cara”, escriu Steiner. Ens miren descaradament. Ell ho provocava. Prenia directament una posició d’avantatge sobre els seus models quan de tant en tant els dibuixava assegut a la part alta d’una escala. De tota manera, després de l’experiència de la presó, els nens i nenes van gairebé desaparèixer del seu repertori temàtic i l’element eròtic es va tornar menys evident.

Schiele va dramatitzar la seva experiència a la presó, però després de l’episodi va viatjar a Caríntia i després a Trieste per recuperar-se i perquè li agradava viatjar. Aquest assumpte no va malmetre la seva carrera. En el mateix any, va exposar novament a Budapest, Munic, Colònia i Viena, i els col·leccionistes es van interessar pel seu treball, el que va suposar una millora de la seva situació financera. Es va traslladar a un estudi a Viena i portava una vida més frívola. Va invertir els guanys de les seves vendes en roba cara, va poder satisfer els seus gustos per la moda, diverses fotografies preses el 1914 mostren un Schiele en la seva inclinació per les poses vanes, amb barrets i vestits, una manera de viure que la seva mare no podia entendre perquè en aquest moment la seva família tenia seriosos problemes econòmics. Es va convertir en un jove dandi en contrast total amb una obra excèntrica, inquisitiva, escandalosa, que no era còmoda per a la alta burgesia i l’aristocràcia vieneses, al menys d’una manera tan gràfica, però sembla que els va agradar i la va comprar, potser precisament perquè reflectia la seva intimitat o els seus desitjos més inconfessables o la seva atracció per la part fosca de l’ànima que comparteixen molts éssers humans. El 1913, la carrera artística d’Schiele es va consolidar. Va esdevenir membre de la Federació d’Artistes Austríacs (el president era Klimt) i va exposar en importants exposicions, entre elles la Internacional de la Secessió de Viena, i les seves obres exposades a les ciutats alemanyes de Berlín, Munic, Hamburg i Stuttgart. El 1916 la revista Die Aktion li va dedicar un número sencer.

Titelles

Els especialistes en Schiele han sostingut durant molt de temps que el treball de l’artista es basa en una mitologia íntima extreta del seu inconscient del qual n’emergeix una mena de maníac demoníac. Hi haurà alguna cosa d’això, però hi ha més premisses. L’historiador de l’art, Arthur Roessler, que va encoratjar i va patrocinar als joves talents i, en particular a Schiele, va escriure que “les seves figures estilitzades i expressives, les seves figures exòtiques, provenen de les titelles del teatre d’ombres de Java. Ell solia jugar amb aquestes figures durant hores, tenia habilitat per manipular els prims pals que movien els titelles des del principi. I la figura que més li agradava era la més grotesca, la d’un dimoni de perfil desenfadat. Va quedar fascinat per aquesta figura i les altres figures d’ombres que li van deixar una profunda impressió”. Així mateix, cal destacar que li agradava la dansa, veure les contorsions dels ballarins el motivava i admirava especialment a Ruth Saint Denis, una ballarina nord-americana que estava a Europa en aquest moment, els seus moviments acrobàtics, el seu erotisme misteriós, els seus gestos angulosos casaven amb la definició artística del cos humà que pintava Schiele.

Edith

Egon Schile. Edith Schiele (1915). Moderne Kunts, La Haya

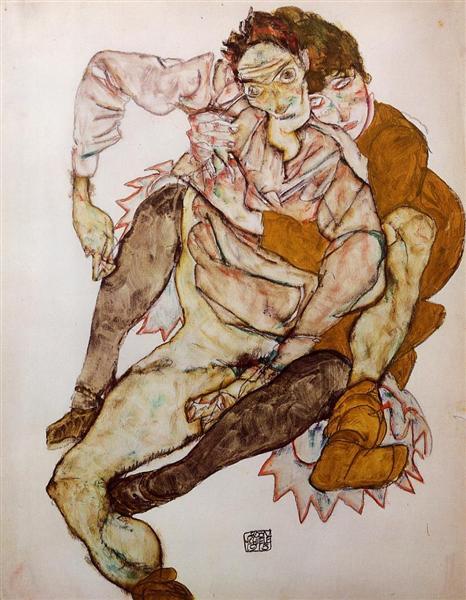

El 1914 va conèixer dues germanes, l’Edith i l’Adele Harms, dues boniques joves de classe mitjana, filles d’un empleat ferroviari, que vivien davat de casa seva, a l’altra banda del carrer. Ell els hi feia poses estranyes des de la seva finestra, o udolava “com un indi” per atreure la seva atenció. Les va convidar a excursions i passejades i l’atracció per l’Edith es va tornar cada dia més forta, però estava vivint amb la Wally. L’Edith era una dona atractiva els trets de la qual s’adaptaven idealment a l’estil de retrat de l’artista. Era esvelta, amb un rostre clàssic, amb barbeta punxeguda i trets femenins. Li va fer un retrat que ha despertat molts comentaris (imatge superior). Té poc a veure amb les dones descarades i desafiants que pintava, és tot el contrari, sembla una nina o una joveneta burgesa insípida. Dècades més tard, l’Adele, la germana de l’Edith, va expressar la seva indignació perquè Schiele li havia donat una imatge de dona estúpida. Potser que l’inspirés tendresa, ella esdevé una invitació a un altre tipus de vida, un potencial de felicitat casolana. De totes maners, cartes datades entre el 1914 i 1915 suggereixen que va estar indecís durant un llarg període de temps entre les dues dones i aquesta indecisió la va plasmar en la seva obra.

Va fer diverses obres que mostraven a dues noies entrellaçades en una abraçada eròtica. La seva solució per a l’embolic en què s’havia ficat va ser proposar una mena de ménage a trois i passar les vacances junts. Inicialment, va pensar que si es casava amb l’Edith podria continuar veient a la Wally, seva musa i model, després del matrimoni, però ni la Wally ni l’Edith van compartir el seu punt de vista. L’Edith estava gelosa i finalment va exigir una decisió definitiva per part d’ell. El seu somni utòpic d’una existència sense problemes amb les dues i evitar un compromís únic i exclusiu es va esfumar. Es va decidir per l’Edith i va descriure el seu matrimoni com “avantatjós” ja que l’Edith provenia d’una respectable família burgesa. L’Edith fou educada en un convent i aviat va descobrir que no li agradava especialment posar per a Schiele.

Sembla que Schiele se sentia culpable per la Wally o be la trobava a faltar. Ella l’estimava, li havia donat tot el suport durant l’assumpte de Neulengbach i la seva relació no era només la d’un artista i la seva model. L’obra Death and the Maiden expressa el dolor per la pèrdua de la Wally amb una abraçada desesperada. El fons és d’un color òxid irregular amb zones verdoses, amb un llençol blanc que suggereix un sudari i que acull la parella. Típic del seu estil, les dues figures reclinades semblen d’alguna manera suspeses a la tela. L’home, vestit amb una túnica fosca, és reconeixible com el mateix Schiele, mentre que la dona és la Wally. El seu cap descansa sobre el seu pit i l’abraça. Ell fa el gest de consolar-la amb tendresa, però la seva mirada desprèn la tristesa i l’horror pel que inevitablement succeirà: la deixarà per casar-se amb una altra dona. Després de la separació, la Wally es va oferir com a voluntària per a la Creu Roja. No es van tornar a veure mai més. Ella va morir d’escarlatina a Dalmàcia.

Praga

Egon Schiele. Embrace. Egon and Edith Schiele (1915). The Albertina Museum, Viena. Foto: Wikiart

Estem en plena Primera Guerra Mundial. Pocs dies després del seu casament amb l’Edith, el 1917, van partir cap a Praga on estava destinat per complir amb el seu servei militar. L’Edith el va acompanyar i inicialment es va instal·lar a l’Hotel París i va fer la seva vida més suportable quan podia sortir de les instal·lacions militars. Després d’una formació militar bàsica va tenir la sort que no l’enviessin al front i va tornar a Viena, però, a l’any següent va ser destinat a Mühling al sud d’Àustria com a empleat en un camp de presoners per a oficials russos, alguns dels quals va retratar.

Egon Schiele. Russian Prisoner of War. Grigory Kladjishuli (1916). Art Institute of Chicago. Foto: Wikiart

Portava un diari de guerra detallat. En una de les entrades va escriure:

Per a mi personalment, el lloc on visc m’és indiferent, és a dir, a quina nació pertanyo, o millor dit, a quina nació visc. En tot cas tendeixo molt més a l’altre costat, és a dir, als nostres enemics -els seus països són molt més interessants que els nostres- aquí tenen llibertat real i tenen més pensadors que nosaltres. Però, què es pot dir de la guerra ara? Cada hora que continua és una llàstima.

Schiele no era un apolític, però no es va mostrar entusiasmat amb la guerra des del principi. Les idees de la força com a nació li eren alienes. Per a ell, la guerra representava simplement la miserable mort de centenars de milers de persones. Odiava els uniformes, els soldats i els oficials, els clergues i tot tipus de col·lectivisme. Li va portar molts intents i moltes sol·licituds oficials perquè fos destinat prop de Viena, on realitzava treballs d’oficina, la qual cosa significava que podia viure a casa seva i no en barracons.

Paisatges i plantes

Egon Schiele. Four Trees (1917). Belvedere Museum, Viena. Foto: Wikicommons

Totes les coses estan mortes en vida.

Aquest eslògan era l’estat d’ànim existencial de Schiele en els anys anteriors a la guerra i va ser només a partir de 1915 que les seves figures ja no són tan turmentades. Steiner creu que és “com si la violència de la guerra hagués superat les seves pitjors visions, i els poders imaginatius de l’artista estan ara absorts en la possibilitat de restaurar la totalitat del món. Els seus paisatges i les seves escenes urbanes són el millor lloc per veure aquest procés en funcionament”. Encara que continuïn essent llòbrecs i melancòlics, la seva paleta es torna més càlida, com és ara a Four Trees. Les plantes i els paisatges urbans van esdevenir el seu nou tema. Va poder influir que la seva esposa Edith com a model ja no va poder satisfer permanentment -o es va cansar- de les demandes obscenes d’un artista que no coneixia tabús. Va intercanviar les figures per plantes, sense perdre mai la traça humana. Va aconseguir un mètode a través del qual les plantes i altres subjectes eren sotmesos a un tractament antropomòrfic. Li va escriure al col·leccionista Franz Heuer el 1913:

També faig estudis però trobo, i sé, que copiar de la natura no té sentit per a mi perquè pinto millors quadres de memòria, com una visió del paisatge – ara principalment observo el moviment físic de muntanyes, aigua, arbres i flors. A tot arreu un recorda moviments similars fets per cossos humans, moviments similars de plaer i pintura a les plantes. Pintar no és suficient per a mi. Sóc conscient que es poden utilitzar colors per establir qualitats. Quan un veu un arbre de tardor a l’estiu, és una experiència intensa que involucra tot el cor i l’ésser; i m’agradaria pintar aquesta malenconia.

Egon Schiele. Sunflower II (1909). Historiches Museum, Viena. Foto: Google Art

Aquest acostament a la natura com una figura antropomófica es pot veure a l’obra Sunflower II. Així la descriu Steiner: “En un estil comparable a les pintures de figures d’aquest període, la flor alta i delicada ja no apareix embolicada en un capoll decoratiu o línies ornamentals, sinó que sembla aïllada, exposada. La forma en què cauen les grans fulles del gira-sol recorda els gestos humans. El format vertical, el colorit i el repertori gestual quasi humà fan del gira-sol una imatge de sentiments elegíacs. Un arbre sense fulles sobre un fons gris gelat, amb un angle estrany que suggereix un moviment que recorda als moviments extàtics i expressius de la dansa, el tema és simple fins al punt de la pobresa. Schiele aconsegueix convertir-lo en una metàfora de la tristesa i la fugacitat”.

Paisatges urbans

Egon Schiele. Deat Town VI (1912). Kuntshaus, Zurich

Per al Futurisme i el postimpressionisme francès, moviments artístics contemporanis a Schiele, la ciutat, el trànsit, la gent i l’enrenou eren crucials, en canvi, ell detestava tot això. Li encantaven els pobles. Va viure a Viena, però sempre que va poder, fugia i es traslladava a petits llogarrets. Com a home d’humor canviant, després, el posaven trist:

Vaig anar a pobles que semblaven interminables i morts, i vaig sentir pena.

De totes maneres, Schiele era un home del seu temps i tal com explica Steiner, la predilecció per les ciutats rònegues o tancades en un pintoresc somni de la Bella Dorment expressava perfectament el gust pel decadent, tan característic de l’art de fin de siècle, particularment el Simbolisme. La malenconia i la decadència eren populars. Però a diferència dels simbolistes, a Schiele no li interessava principalment la vellesa dels pobles i ciutats: “La tristesa dels seus pobles negres i morts no té res a veure amb l’observació i estetització del declivi i la decadència històrica. La ciutat morta o negra és per a ell l’epítom fenomenològic d’una condició a la ment humana (…) Al prescindir de la delimitació precisa del lloc, o de la topografia verificable, i al concentrar-se en les ‘expressions facials’ de les cases i pobles, Schiele estava creant a última instància una paràbola visionària de l’experiència antiurbana”.

Egon Schiele. The old city III (1917). Neue Gallery, Nova York. Foto: NG

El pintor austríac Albert Paris Gütersloh (1887-1973), es va adonar que els éssers humans no poden viure en aquests pobles. Va sentir que l’efecte era pel resultat de la perspectiva de vista d’ocell que utilitzava Schiele: “Ell para l’atenció a una ciutat a la que mira des de dalt i les vistes de la ciutat morta són fetes en escorç. Perquè cada poble sembla mort vist així. El significat ocult de la vista d’ocell s’ha revelat inconscientment …” Gütersloh va assenyalar que la font d’inspiració d’Schiele era una visió interior, aquests pobles es converteixen en projeccions “dels terribles convidats que de cop i volta visiten l’ànima de mitjanit de l’artista”. Aquest mètode el va aprendre a Krumau. Va dir:

Allà aprens a mirar el món des de dalt; i l’insòlit d’aquesta manera de veure, es que la vista frontal, adquireix un valor pictòric i gràfic …

Quan disposa les figures humanes retorçades en vertical, vistes des de dalt a la composició, es causa un efecte desestabilitzador, els cossos trontollen o suren en suspensió, deixant-los al descobert, exposant-los a tota indiscreció. En els paisatges urbans, per contra, la vista d’ocell no indueix a la suspensió sinó a la construcció, tal com es veu en l’arranjament de les línies verticals, horitzontals i diagonals. Són les juxtaposicions i relacions específiques de línies i espais les que produeixen els valors pictòrics i gràfics als quals es referia el mateix Schiele. No obstant això, al mateix temps, aquestes interaccions produeixen una textura decorativa, gairebé artesanal en les pintures i en els dibuixos, una dimensió il·lustrativa que, encara que certament explora els valors atmosfèrics amb gran sensibilitat, queden lliures de toda formalitat convencional i simbolisme.

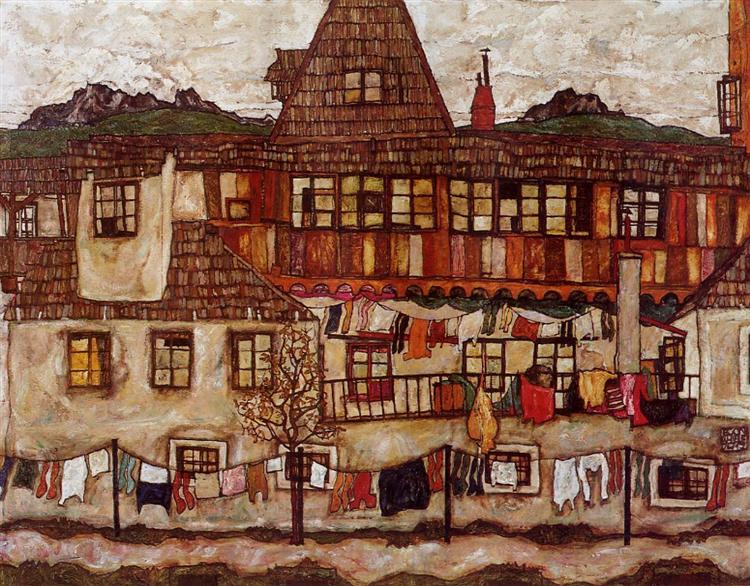

Egon Schiele. Suburban House with Washing (1917). Col.lecció privada. Foto: Wikiart

Pel seu color i disseny aquests paisatges urbans semblen tapissos. Esdevenen paisatges on no hi ha indústria, no hi ha xemeneies de fàbriques fumejants o altres signes de tecnologia. Per a ell la ciutat i la vida moderna, la nova civilització, no té cabuda en el seu art. No era simple nostàlgia, sinó una una actitut coherent amb la línia Ver Sacrum de la Secessió de Viena, el que el va portar a creure en les restes d’una civilització noble i aquestes restes només podrien conservar-se amb l’ajuda de les arts i les artesanies. Fins i tot va voler crear una associació d’artistes anomenada Kuntshalle que no es va poder materialitzar en temps de guerra.

Maternitat i mort

Egon Schiele. Poster per a la 49th Secession Exhibition (1918). Museum of Modern Art, Nova York. Foto: MoMA

Ja instal.lat a Viena, a la primavera de 1917, va exposar a diversos espais i ell mateix va ajudar a organitzar una exposició sobre la guerra. Al febrer de 1918 va morir Gustav Klimt. Havia estat el guia de tota una generació d’artistes vienesos i, fins al final, va seguir sent un artista venerat per Schiele. En aquells dies, el nom de Schiele era cada dia més conegut i ell es veia a si mateix com el successor legítim de Klimt. En la 49a Exposició de la Secessió de Viena, Schiele va ser celebrat com a líder de la comunitat artística vienesa, ell mateix en va dissenyar el cartell i les seves pintures i dibuixos van causar una gran impressió en la premsa internacional. Va ser el seu major triomf, estava en el seu millor moment i era molt conscient del seu nou estatus.

Egon Schiele. Mother and Two Chidren (1917). Belvedere Museum, Viena. Foto: Artsy

El seu matrimoni amb Edith i l’acceptació de viure en una normalitat típica de classe mitjana van provocar un canvi en l’enfocament de Schiele sobre el tema de la maternitat. Ja no es tractava de la seva pròpia infància i el conflicte amb la seva mare, ja no es tractava d’una experiència personal que sentia que havia estat tràgica. A Mother and Two Children assoleix un nou to lliure de conflictes, de mort, més serè. L’anhel d’amor i seguretat que Schiele només podia expressar simbòlicament a través de l’absència i reprovació en els seus primers quadres sobre la maternitat, ara ha estat reemplaçat per l’esperança de construir una família, la seva.

Egon Schiele. The Family (1918). Belvedere Museusm, Viena. Foto: Artsy

The family va ser el seu últim quadre important. Schiele es mostra a si mateix nu assegut en un sofà. Davant d’ell es posa a la gatzoneta una dona nua amb un nen petit entre les cames. El color més dens que mai, aporta l’efecte de tridimensionalitat, crea una sensació de volum físic i accentua la presència de les figures, les fa més sòlides. Ja no són com titelles suspeses en un espai buit. Una pintura revitalitzant, en comparació amb les anteriors. Veiem l’home que ha deixat enrera malícies i paranoies, esperançat i confiat, a punt de formar una familia pròpia, tot i això, tota la pintura desprén una intrínseca melanconia, principalment el rostre de l’Edith, potser el pintor intuïa que aquesta felicitat no arribaria. El 28 d’octubre de 1918 la seva dona Edith va morir de grip espanyola. Estava embarassada de sis mesos. Tres dies després, el 31 d’octubre, va morir ell, també de grip espanyola.

Àngels Ferrer i Ballester

Principals fonts consultades:

Reinhard Steiner. Egon Schiele 1890-1918. The Midnight Soul of the Artist. Benedikt Taschen: Köln, 1993

Leopold Museum, Viena

The Albertina Museum, Viena

Neue Gallery, New York

Belvedere Museum, Viena

Film: Exzesse. Dir: Herbert Vesely. Amb Mathieu Carrière, Jane Birkin i Christine Kaufmann